Scholarly CVs are long, there's no denying it, so it's not surprising that Paul N. Courant's CV stretches a good twelve feet from end to end. What is surprising is that what is likely to be Courant's single greatest contribution to scholarship isn't mentioned in his CV at all: development of one of the largest digital libraries in the world, the HathiTrust.

Act 1

Ten years ago, Larry Page (BS '95), co-founder of Google, contacted the University of Michigan to offer a rather unconventional gift to his alma mater: scans of the University's entire collection of 7 million books, free of charge. Page had just developed a new scanning system that, unlike previous scanners, could produce text-searchable copies at unprecedented scale (millions of books per year rather than thousands), without damaging the books themselves.

|

'Hathi,' the Hindi word for elephant, signified the universities' aspirations: a large collection with a powerful search engine and a long memory. |

Courant, an economist then serving as provost—the chief academic officer of the University—remembers running a standard cost-benefit analysis. "What's it going to cost?," he asked the University's head librarian, Bill Gosling. "What's in it for us?" Beyond some staff time, Gosling explained that the costs would be borne by Page's company. But the benefits, says Courant, "were at least very useful, and possibly super-useful."

For starters, digitization would provide a backup copy of the entire library, ensuring the longterm preservation of everything in the collection. "In the print world, preservation's assured by the fact that there are a lot of copies out there, people toss them on the shelf, and they rot slowly," says Courant. But what about historic collections now out of print? Or texts written by hand, before the invention of the printing press? Or limited edition print runs? Think of what happened to the priceless library of Timbuktu last January, or the Library of Congress in 1814, or the great Library of Alexandria, or countless other small libraries near and far. Libraries are safe, but hardly invincible, and preservation is a paramount concern.

Digitization would also make it possible to run detailed text searches of all of the library's collections. In the coming years, a descendant of the University of Michigan's first African-American student-athlete would use the HathiTrust Digital Library to locate news stories about her ancestor. An undergraduate honors student would use the HathiTrust to search the complete correspondence and writings of President Eisenhower for a thesis on Eisenhower's attitudes toward nuclear weapons. And the U.S. Patent and Trade Office would use the HathiTrust to locate copies of patents lost in an 183 fire. Full-text searches would lead citizens, scholars, and policymakers directly to the material that interested them, enabling new and important discoveries.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, digitization would allow the libraries to offer free online access to all public domain works—generally works published before 1923, including almost all of the University's rare historical collections—for anyone with an internet connection. What Wikipedia did for the encyclopedia, digitization could do for the library—but scholars would be able to access the original source documents themselves, not just a summary of their contents. It would be a powerful public service to the world. "That's what libraries do," says Courant. "That's what universities do."

So after some back-and-forth haggling over the quality of the scans and access to original digital copies of each, the University of Michigan accepted Larry Page's offer to digitize its collections. And several years later, after stepping down as provost, Courant was appointed dean of libraries, a post that would allow him to continue to work on the Google scanning project.

Act 2

When the Institute of Public Policy Studies recruited Courant to teach forty years ago, the University of Michigan was a worldwide pioneer in computing. That means U-M had a few ginormous, and very expensive, computing towers that faculty could use for 15 minutes a pop. Today, nearly every University stakeholder has at least one personal computer, often more, and internet access is ubiquitous in the academic the world.

When the world changes that dramatically, one can expect brand new problems, and brand new opportunities. "The invention of digital information technology totally transforms the way in which you might expect scholarship to be published and libraries to do their business," explains Courant. "How do we design libraries so we can really take advantage of this treasure-trove of digitized information?" As dean of libraries, Courant would be in the perfect position to solve those problems, and to grasp those opportunities—and he knew it.

Courant was certain that the University of Michigan could build a workable system for sharing its digitized collections. And that Stanford, Harvard, Oxford, and the New York Public Library—other early partners in Google digitization—could each do the same. But if the University of Michigan pooled its collections and resources with other libraries, he reasoned, couldn't they create a single, huge repository that would reduce institutional costs and provide streamlined access for users all around the world?

Courant was certain that the University of Michigan could build a workable system for sharing its digitized collections. And that Stanford, Harvard, Oxford, and the New York Public Library—other early partners in Google digitization—could each do the same. But if the University of Michigan pooled its collections and resources with other libraries, he reasoned, couldn't they create a single, huge repository that would reduce institutional costs and provide streamlined access for users all around the world?

Courant, working with colleagues at Indiana University, put together a business plan to do that, shopped it to the other members of the Big Ten and to the University of California system, and in the course of a few months, launched a collective digital library, the HathiTrust.

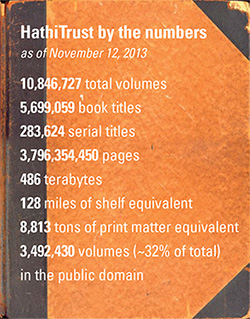

Today, the HathiTrust—by far the largest digital library anywhere—includes 80 academic library members, contains 10.8 million volumes, and welcomes 50,000 users each weekday (25,000 on weekend days). Those users run advanced searches of the entire collection. They create their own sub-collections, like the collection of 912 Islamic manuscripts compiled by one savvy user. And they read out-of-print books, from one virtual cover to the next, on computers and mobile devices around the world. In just a few years, HathiTrust has become an indispensible part of the scholarly infrastructure.

Act 3

To be true, Act 3 hasn't been written yet. Courant has returned to the faculty in the Ford School, where he'll work to further a pretty hefty vision for digital libraries and scholarly publishing. Known as an outspoken critic of overpriced scholarly publications, Courant says now that HathiTrust has been created, it makes other things possible like, for example, "creating a platform to allow people to publish open-access journals that will be preserved indefinitely."

HathiTrust's robust preservation strategy allows the consortium to offer permanent storage of scholarly journals, but the trust will only do that for open-access titles that are shared freely. Courant isn't against a little "shameless commerce," he says (HathiTrust sells reprints of some out-of-copyright items, including its top-seller, an 1860s-era guide to beekeeping), but the University of Michigan alone spends more than $10 million a year on journal subscriptions, and for smaller academic institutions—whether in Kenya, Kazakhstan, or Kansas—those fees put important scholarly research well out of reach.

Below is a formatted version of this article from State & Hill, the magazine of the Ford School. View the entire Fall 2013 State & Hill here.