Sherry Suttles (MPP ’71) made history as the first Black woman city manager in the United States.

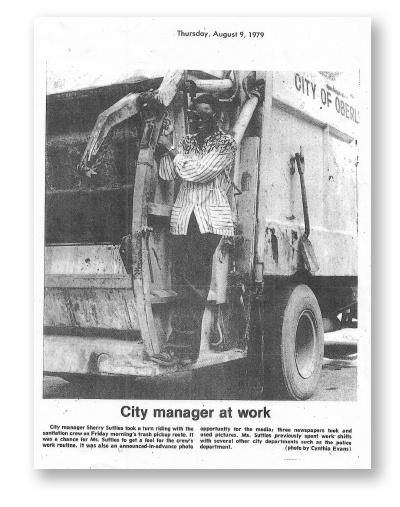

That was a goal Suttles had set for herself soon after graduating in the first class of Master of Public Policy degrees awarded by U-M’s Institute of Public Policy Studies (IPPS) and then accomplished eight years later when she became city manager of Oberlin, Ohio, in 1979.

Perhaps by design, it’s a milestone that does not have the same widespread recognition received by trailblazers in other occupations. City managers often work out of the limelight, handling the critical but mundane issues of running cities—from dealing with abandoned lots to zoning. But the first generation of Black city managers in the late 1960s and 1970s came into office at a crucial time, after urban race riots had shaken Harlem, Detroit, Newark and other American cities. The Kerner Commission had warned that the nation was “moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal,” raising awareness and urgency around strengthening cities and addressing longstanding inequities.

Suttles, inspired to prioritize education by her mother, majored in government at Barnard in 1969. The usual jobs for women—nurse, teacher, social worker—did not appeal to her. Suttles had seen Malcolm X and marched with Martin Luther King Jr. in Detroit. She felt it was her generation’s responsibility to make change happen. “I had to have a job that could allow me to address the issues that were being raised. I wanted to have the boots on the ground, get in and make changes,” Suttles recalls. After graduating, she was among the first Urban Fellows in New York City—a program which introduced recent college graduates to municipal government.

However, it is the Ford School (IPPS at the time) that Suttles credits with launching her career in city management. Wanting to be closer to her home city of Detroit, she enrolled at IPPS when the Institute was just launching. By Suttles’ recollection, it was a small, and compared to other schools, a very diverse program. “It was like a brother-sisterhood,” says Suttles. Many of the Black students who were in Suttles’ class were part of a program run by the International City Management Association (ICMA), in partnership with the University of Michigan, responding to the need to diversify city halls with training and placement opportunities in municipal administrations.

“When I’m coming here ‘militant’—and that’s in my bloodstream—I can only do so much of the routine basic governmental services that the job requires. I have to get out and help my people.”

IPPS was in the process of transitioning from public administration towards public policy—as the very first such graduate program in the U.S. “Despite the fact that our curriculum was more geared toward people who might do federal-level policy, we looked for opportunities for people who wouldn’t be mailing federal checks from DC but rather spending that money in local communities,” recalls professor emeritus John Chamberlin. “The students who came in knowing that they wanted to do city work learned a lot about how the federal money was being distributed to cities and how to spend federal money intelligently and with an impact.” Moreover, the program had strong ties to Detroit, which at the time was an important laboratory for the next phase of rebuilding cities. Its former mayor, Jerome P. Cavanagh, came to campus frequently to discuss the problems of cities.

Inspired by what she saw her classmates doing, Suttles reached out to ICMA. “I said ‘Listen, I’m not in your program but I’m Black, I’m female and I want to be a city manager,’” she recalls. Suttles went to work at ICMA and then began a string of positions in California, including as assistant city manager in Menlo Park and executive assistant to the city manager of Long Beach.

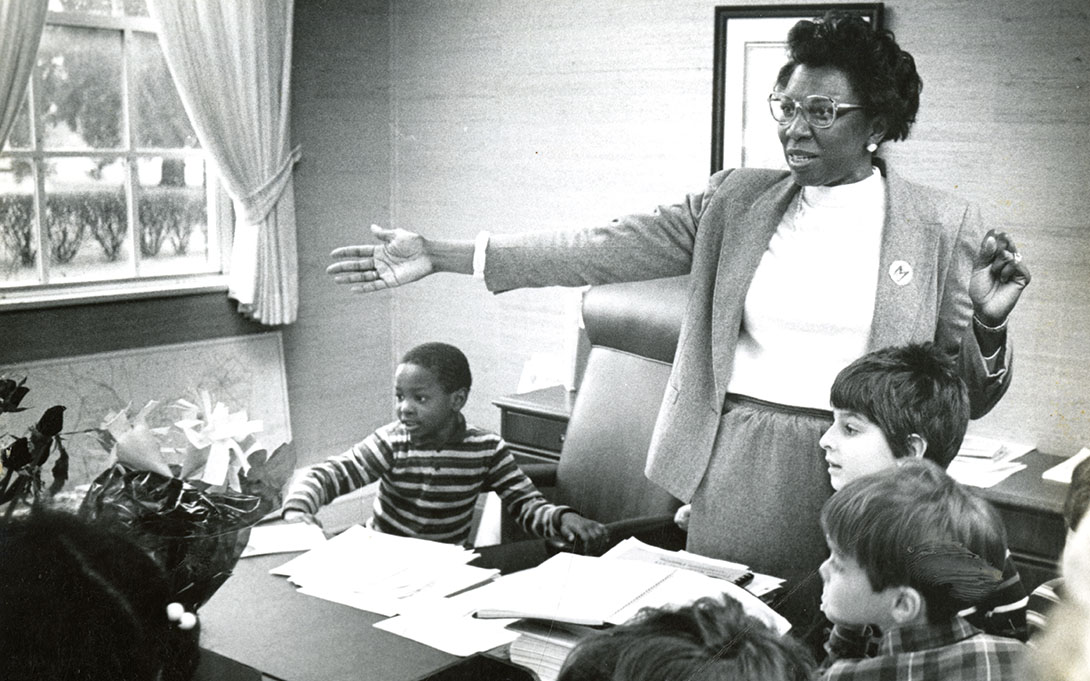

By the end of the 1970s, Suttles felt ready to be a city manager herself and applied to positions in over 20 cities until she was hired by Oberlin in 1979. During the two and a half years she was Oberlin’s city manager, Suttles hired the city’s first Black police chief, Bob “BJ” Jones, who held the position for 20 years and became a fixture in the town; she signed up business owners formerly reluctant to work with town government on a downtown revitalization effort; she managed the city’s interests when a commercial printing house relocated from Cleveland to Oberlin and became an important local employer; and she spearheaded the creation of the Oberlin Youth Council, which was a mixed gender and race group that involved recreational activities, social service, and fundraising.

From her tenure in Oberlin, Suttles is most proud of obtaining grants to help the Black community resolve housing issues. For Suttles, it was a crowning touch and one of the signature moves that the first generation of Black city managers were implementing in the 1970s. “Some didn’t have toilets, had bathrooms in the backyards, had roof problems,” she recalls. “We were gravitating towards our part of the city that was not getting equitable treatment.”

Suttles went on breaking gender and racial barriers in several of her subsequent municipal management jobs in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina; Lawrence Township, New Jersey; and Guilford County, North Carolina. Her tenure tended to last a couple of years as she sought to quickly change what she could and then move on to somewhere else. “When I’m coming here ‘militant’—and that’s in my bloodstream—I can only do so much of the routine basic governmental services that the job requires. I have to get out and help my people.”

That motivation did not end with her retirement from public administration. In 2000, Suttles founded the Atlantic Beach Historical Society, which centered the South Carolina town’s revitalization efforts by documenting its unique history and character as a thriving Black-owned beach town during the segregated 1940s and ’50s.

Now, at 76, she is heading her second nonprofit dedicated to community development and preserving Black history. Her newest venture, the Gullah Geechee Group, combines preserving the culture, religion, and music of Black communities in the barrier islands off the east coast of Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina, with efforts to reclaim and retain Gullah Geechee land. Suttles hopes to unlock wealth and allow residents to make progress by helping resident families obtain clear title to properties that belonged to their families but were lost through lack of legal wills. Suttles has just finished grant applications for about $200,000 to provide families with mediation and legal assistance in reclaiming heirs’ property. If it comes through, she says, perhaps then she will retire.

By Miriam Wasserman

More in State & Hill

Below, find the full, formatted fall 2023 edition of State & Hill. Click here to return to the fall 2023 S&H homepage.