It was the summer of 1971 when the first mandated round of redistricting was taking place across the nation. A series of Supreme Court decisions in the '60s had directed states to create new legislative districts every ten years to reflect population shifts revealed in decennial census counts. The goal was honorable enough: one person, one vote; but so little instruction was offered on how to accomplish the task that it practically invited abuse.

A group of faculty and graduate students led by Ford School instructor and U-M research professor Steve Pollock spent the summer experimenting. The challenge they addressed: could linear programming help craft districts with population equity and contiguity, as well as objective qualities like compactness or competitiveness?

Ford School Professor John R. Chamberlin, a member of that operations research group, explains how they tested a number of mathematical models by writing computer codes and running them on the University of Michigan's then-state-of-the-art mainframe, a six-foot tall IBM 360/67M. When they used up their own monthly computer allocations, they begged and borrowed leftover time from other faculty.

By mid-summer, though, the group discovered that redistricting was more than an optimization problem: it was a power play.

At a political fundraiser that summer, Chamberlin heard that the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party wanted a new district map for the state's four-member Coahoma County Commission. A Houston consulting firm had drawn new districts in response to the Supreme Court mandate, but each had a white majority. The result would be simple enough to predict. No African American commissioners, in spite of the fact that blacks made up 40 percent of the county population. Chamberlin and his colleague, Bruce Bowen, were asked to design an alternative plan. Theirs put black majorities in two of the four districts. The case went to court, and, "the south being what it was in those days, we lost," says Chamberlin. "That was my first taste of the political power inherent in drawing districts."

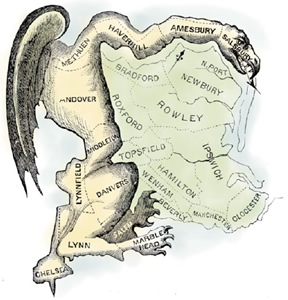

Redistricting for political advantage isn't really a new phenomenon, and wasn't in the '70s. Two hundred years ago, Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry drew some very creative state senatorial districts that would give his party a decided advantage in the 1812 elections. As a result of his new district maps, roughly equal numbers of votes for each party resulted in 29 Democratic-Republican seats compared to a paltry eleven seats for the Federalists. Gerry's own district was so misshapen that it reminded the editor of the Boston Gazette of a dragon. An artist visiting his office suggested it was more like a salamander. The editor rebounded by naming it a Gerrymander. And the district, and term, earned national fame when its contours were embellished with the head, folded wings, and sharp talons of a fire-breathing dragon.

|

|

Two hundred years ago, Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry drew some very creative state senatorial districts to |

Still, the 1970s saw lawsuits about redistricting exploding across the nation. These suits challenged newly contoured districts using the Fourteenth Amendment and the Voting Rights Act. Although the Voting Rights Act proved a potent weapon against racial gerrymandering, says Chamberlin, the Court showed no appetite for tackling gerrymandering for partisan advantage. "A decade later they would rule that partisan gerrymandering could be challenged in the courts, but they backed away from rejecting redistricting plans that most observers believed blatantly partisan—with district shapes that outdid the work of Elbridge Gerry."

With the 2010 census just behind us, district lines have been drawn again—all across the country. The most contorted districts are generally designed to maintain power for the leading party in one way or another. To do this, they make other sacrifices.

"Many of the new Michigan Congressional districts do incredible violence to city, county, and township boundaries," says Ford School alumnus Larry Horwitz, who drew the 1971 districts—neatly, compactly, and without dividing municipalities—for Detroit's state house. "People live by these minor civil divisions, so an important value in redistricting is for people to know which district they're in and who their candidates and eventual representatives are. District 14," Horwitz explains, "splits West Bloomfield Township [population 64,690] into two different districts to establish a very narrow land link between Pontiac and the rest of the 13th Congressional district that runs all the way to southwest Detroit."

While some of these contorted districts may be attempts to ensure that minorities don't lose legislative representation (a later U.S. Supreme Court case—the Court's non-retrogression standard—insisted that new districts couldn't be designed to reduce the voting strength of minorities), many, Chamberlin avers, are likely political maneuvers.

Packing political opponents into a limited number of districts allows the party in charge to maintain a small but comfortable majority in many more—maintaining and increasing their power in the legislature. Drawing lines that move an incumbent out of his home district, or that force two party colleagues to run against each other has a similar effect, says Chamberlin. "These redistricting techniques can tilt the playing field for a decade."

John J.H. "Joe" Schwarz, a visiting lecturer at the Ford School and former U.S. Congressman (R-MI), understands how district lines can impact incumbents. Schwarz's district was redrawn to pit him against a candidate more to the taste of the far right wing, which then financed that candidate's campaign to the tune of millions. Other moderate colleagues, he says, have been reapportioned out of their districts, too. "These are some very, very good representatives," says Schwarz, "not bad or ineffective members."

The gerrymander casualties Schwarz refers to are Democrats and Republicans—good guys on both sides of the aisle. Asked to talk a little about bipartisanship in Congress, Schwarz says, "Sure. Not much of it exists."

One of the effects of creating districts that aren't competitive is that there's little incentive for incumbents or challengers to pursue centrist agendas. Schwarz has seen it firsthand. In Congress, he dined with a Democratic colleague, comparing committee notes and catching up. A few days later in the Caucus Room, a fellow Republican confronted him about it. "Don't you know she's a Democrat?"

Of course I did, says Schwarz. "The atmosphere in 2006 was virulently partisan."

The foreseeable forecast? More of the same. "The 2011 redistricting has turned gerrymandering into an art form," says Schwarz.

Below is a formatted version of this article from State & Hill, the magazine of the Ford School. View the entire Spring 2012 State & Hill here.