Much of America is mesmerized by the recent and remarkable torrent of money flowing into the 2012 elections by organizations with buoyant names like Restore Our Future and Make Us Great Again. These contributions have dramatically overshadowed expenditures by the candidates and political parties that have traditionally run campaigns. It wasn't always so, explains Ford School Professor Richard L. Hall, who has written extensively on the influence of money in politics and policy.

Prior to the rise of Super PACs, Political Action Committees (PACs) "could contribute such small sums of money to candidates that it was hard to imagine these contributions had much of an impact at all," says Hall. "The better hypothesis was not that PAC contributions were buying something from members, but that they were signaling something to them."

Indeed, Hall's own research with former Ford School colleague Rob Van Houweling and political science alumnus Matt Beckmann (PhD '04) upheld this notion. Just what would those contributions have signaled? That the PAC and political candidate shared similar objectives and that there might be an opportunity to work together on relevant legislation should he or she win.

Super PACs, however, have changed the game entirely.

The rise of independent spending

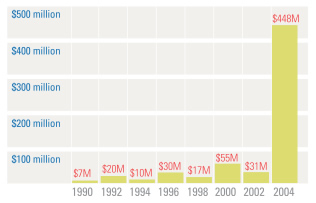

Rich Robinson (MPP '82), director of the Michigan Campaign Finance Network, demonstrated the extent of the phenomenon during his recent guest lecture in John J.H. "Joe" Schwarz's graduate-level course on the legislative branch. Standing behind the podium in the first-floor lecture room of Weill Hall, Robinson opened with a slide on independent spending in federal campaign communications. It looked something like the following chart: Wondering what happened in 2004?

Twenty-five people gave multimillion gifts (from $2–$23 million) to 527 committees, tax-exempt groups that can accept unlimited "soft money" contributions. This helped fuel the explosive growth of brand new entities like America Coming Together, on the left, and Swift Boat Veterans for Truth, on the right.

|

After Swift Boat Veterans and the 527 boom, the next great change in the political financing landscape followed the 2007 Supreme Court decision Federal Election Commission v. Wisconsin Right to Life, which ended the prohibition against corporate "electioneering communications" (advertisements featuring the name or image of a candidate in the weeks immediately before an election). Although corporations still couldn't tell viewers how to vote, they were now free to support ads about the policy stance of candidates for public office.

The birth of the Super PAC

The progress made by John McCain and Russ Feingold's Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA) of 2002 was quickly disintegrating. Independent ads sponsored by nonprofits and 527 committees attacked candidates for public office, but because they didn't use the words "vote for" or "vote against," the courts considered them legal.

Today, independent "social welfare" nonprofits such as Americans for Prosperity and American Future Fund raise unlimited soft money for getout-the-vote campaigns and issue ads, but face tighter limits—and risk losing their tax-exempt status—when they engage in "express advocacy" (ads that explicitly advocate for the election or defeat of a particular candidate). Many smart people have been left wondering, though, if the difference between "express advocacy" and "electioneering communications" isn't at all discernible to the television-viewing voter, why should the distinction matter to the courts?

Fast forward to January 2010, when Citizens United v. the Federal Election Commission blew another hole in the crumbling fortress of campaign finance regulation.

When the Supreme Court sided with Citizens United, ruling that the Federal Elections Commission couldn't prohibit corporations and unions from exercising their free speech rights in the form of independent expenditures, the drawbridge was lowered. Then SpeechNow. org v. the Federal Elections Commission, just a few months later, allowed corporations and individuals to pool funds to amplify their messages.

Super PACs were born.

What it all means

"The consequences for our campaign finance system are huge," says Hall, who is certainly not alone in thinking that these matters may need to be revisited by the courts. Beyond the fact that Super PACs have allowed a few wealthy donors to keep their favorite presidential candidates in the game long past the point when the Republican presidential candidate would normally have been selected, says Hall, they've spanned an important gap that once existed between wealthy donors and the political candidates they favored.

A decade ago, large contributions from corporations and unions would need to go through the party, "so there was a separation between the money going to the party and whatever pressure or obligation the individual member [of Congress] might feel as a result of the gift," says Hall. "Now, to the extent that you have individuals or organizations that are funding three-quarters of some candidate's campaign, which they could easily be doing in some of these Congressional elections, that's got to meet the standard of 'appearance of corruption.'"

Stephen Hoersting, vice president of the Center for Competitive Politics, holds a different viewpoint. "Before Citizens United and SpeechNow.org," writes Hoersting in The Jurist, "mainly wealthy interests—large companies with PACs, national unions, and billionaires like George Soros and Mike Bloomberg—could speak out about candidates and politics. SpeechNow. org means that now donors of all sizes can pool their resources to more effectively communicate a message about politics and candidates."

It's true that donors of all sizes are contributing to Super PACs, but there's no denying that the lion's share of Super PAC money comes from a handful of extraordinarily wealthy individuals.

Why should that matter? "People who put money in politics don't do so for selfless reasons," says Rich Robinson. "You have to make the assumption that they're rational economic actors, and they're seeking a return on their investment, on, and after, Election Day." Often, those investments pay off—at least on Election Day. Campaign expenditures have an uncanny tendency to predict the outcomes of elections.

|

|

Joe Schwarz |

Former U.S. Congressman Joe Schwarz (R-MI) agrees. "He who has the wealthiest political sugar daddies wins," says Schwarz, though he doesn't believe it should be that way. "It says utterly nothing about the positions a candidate might take on issues or the candidate's experience in formulating public policy, which, I might add, is extremely important. It says everything about extreme political philosophies who have access to money being able to step in, and control, and ultimately determine the outcome of an election."

While the Federal Elections Commission can't prohibit or limit contributions, it can require Super PACs to disclose the names of their donors. However, donors who contribute to a 501(c) tax-exempt group, which in turn contributes to a Super PAC, can still remain anonymous. The DISCLOSE Act, recently introduced by Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI), would require timely disclosure of contributions. However, with no Republican support, it seems unlikely to pass.

Stephen Colbert, host of the political comedy show The Colbert Report, continues to draw attention to campaign finance with his Super PAC, Americans for a Better Tomorrow, Tomorrow (ABTT), which has raised about $1.1 million to date and garnered tremendous public and media attention. While the vast majority of donors to ABTT have made small gifts, Colbert's attorney, Trevor Potter, recently helped him launch a 501(c) corporation, Anonymous Shell Corporation, which would allow major donors to make unlimited contributions while maintaining their anonymity.

Comedy aside, as of April 5, 2012, OpenSecrets.org indicates that the 408 registered Super PACs have reported raising $153 million—the vast majority of which is fueling invective and lining the pockets of media outlets and ad executives through a slew of negative campaign ads. According to The Washington Post, 72 percent of the ads funded by Super PACs are negative. As the presidential election approaches, and more Super PACs submit their quarterly reports, analysts expect those negative ads and the contributions fueling them to explode. . . .

Interestingly, Super PACs organized by those with liberal affiliations have either been late to the game, less successful, or less active, so far. The 189 Super PACs with conservative affiliations have raised $121 million, while the 86 liberal-affiliated Super PACs have raised $26 million. Because these numbers are still shifting, it's hard to predict how they'll evolve in the coming months. Still, many expect independent expenditures from 501(c)s, 527s, PACs, and Super PACs to top $1 billion in the 2012 campaign.

"I'm old school enough to believe that's not the way it should be," says Joe Schwarz. "I know that it takes money to run a campaign. It's foolish to think otherwise and I'm neither naïve, nor am I a purist. But money with no discernible element source is rolling into political campaigns seemingly endlessly.... That's many things, but democracy it is not."

Below is a formatted version of this article from State & Hill, the magazine of the Ford School. View the entire Spring 2012 State & Hill here.