On August 18, Dr. Dan Kelly published an op-ed in the San Francisco Gate. His friend and colleague, a medical doctor, had died in Sierra Leone after serving an Ebola patient without protective gear. It wasn’t negligence, wrote Kelly, an infectious disease specialist and co-founder of the largest primary care clinic in eastern Sierra Leone. The gear was simply unavailable, and the patients needed help.

When patients are struck with Ebola, a highly contagious disease, the safest place for them is an isolation ward, where they can avoid spreading the illness to friends, family members, and colleagues. While they’re in isolation, patients receive treatment and care from health care workers. But health care workers themselves are not immune. According to a recent WHO report, some 240 health care workers have been infected with Ebola, and more than 120 of them have died as a result. And not only can health care workers catch Ebola, they can spread it.

The issue is a severe shortage of both medical supplies and protective gear, including gloves, gowns, masks, and boots that would keep health care workers safe from catching, and continuing to spread, the disease. That’s where Direct Relief comes in.

Direct Relief, maximizing limited resources

Direct Relief is a non-profit that solicits pharmaceutical and medical companies for donations of medicine, supplies, and equipment, then ships those life-saving materials to front-line clinics around the world. Andrew Schroeder (MPP ’07), director of research and analysis for Direct Relief, helps the organization identify the areas in greatest need to maximize the impact of limited resources and direct aid to the places where it will do the most good. This summer, Nate Gire, a master’s of public policy student at the Ford School, interned with Schroeder to aid in that process.

When Gire began his internship, he didn’t realize he’d be helping the organization craft its response to Ebola. Gire signed on with Direct Relief because he wanted to learn more about how to map data for research and analysis—something he’d been introduced to by a high school teacher. Mapping, says Gire, is a lot like writing effectively about a policy problem, “except that a map is visual, powerful, and awesome.” At Direct Relief, Schroeder often maps data visually — to inform the medical community about urgent supply needs, to inform Direct Relief’s decisions about where to send those supplies, and to understand the complexities of humanitarian interventions as they evolve.

Mapping for decision-making, fund-raising, and transparency

Direct Relief’s mapping efforts are split between proactive and reactive strategies. Proactively, Direct Relief uses mapping to resupply health clinics with materials they regularly need, including midwife kits, antibiotics, and HIV treatment drugs. But when a crisis strikes—a natural disaster, an infectious disease outbreak—Direct Relief jumps into action, and mapping plays a role there, as well. At the time Gire began his internship, the Ebola outbreak was limited to Guinea, but when it spread to Liberia, the Liberian Ministry of Health reached out to Direct Relief for assistance, and Schroeder put Gire’s talents to use.

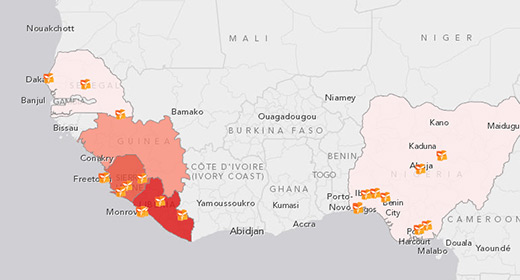

With instruction from Schroeder’s team, Gire created an interactive map, prominently featured on Direct Relief’s web site, using data from the World Health Organization’s Disease Outbreak News bulletins to show the location of all known Ebola cases, the health clinics where many of those patients were receiving treatment, and the areas where Direct Relief had already sent protective gear. The data allows people to quickly understand the scope of the threat. “It’s also a transparency method,” notes Gire. “When donors put their money on the table, they can see exactly where it’s going.”

For Gire, the experience was just what he’d hoped for. It became a cyclical teaching experience, he says. He learned more about mapping by creating the map, he got to observe its impact, and before he returned to the Ford School for his final year of studies, he put together instructions so the map could be easily and accurately updated going forward.

Meeting Millennium Development Goals for health

Interestingly, the Ebola map was a side project for Gire. His main project was to create a map for the One Million Community Health Workers Campaign, a collaboration between the United Nations and the Earth Institute at Columbia University that aims to address the health-related Millennium Development Goals by expanding community health worker training programs in Africa.

“Community health workers,” says Schroeder, “are often the only link to healthcare resources for the poorest communities. You can see their importance right now in the Ebola crisis where they’re performing essential primary care across highly impacted areas in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea, where much of the formal health system may be at risk of severe contraction or worse.” Direct Relief has been contracted by the Earth Institute to do the mapping, says Gire, and the map he worked on will eventually help to identify the locations where these health workers are most desperately needed.

“Direct Relief has consistently been noted one of the most efficient non-profits in the country,” says Gire. “It was really great knowing that I was helping to inform the organization’s decision-making process, as well as the public at large on what their contributions were supporting.”