Two wars dominated the presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson. One was the war in Vietnam, whose escalation in 1964 triggered more than a decade of combat in Southeast Asia and discontent at home. The other was a wide-ranging package of social legislation collectively dubbed the War on Poverty.

Programs like Medicare, Medicaid, Head Start, and food stamps still profoundly affect American society, rather more positively than Vietnam did. But while the dreary economic news of the last few years has led some observers to suggest that we may have lost the War on Poverty, Sheldon Danziger, president of the Russell Sage Foundation, disagrees.

“The War on Poverty sought to raise the living standards of those at the bottom of the income distribution,” says Danziger, one of the country’s pre-eminent poverty scholars, who will officially retire from the University of Michigan in December after 25 years on the Ford School faculty.

“In absolute terms, we have made a lot of progress in the last 50 years….We don’t have the kind of mass deprivation that we had when Johnson declared war on poverty because of the programs it launched and expanded,” Danziger says. “More than 40 million Americans receive food stamps, millions are covered by Medicaid and Medicare, and low-income working families receive the earned income tax credit. Poor children attend Head Start programs and low-income college students receive Pell Grants.”

But that doesn’t mean the goals of the war on poverty have been achieved. “The economy has failed the poor in recent decades,” he says. “No one in the early 1970s would have thought that by 2013, inflation-adjusted earnings would be so little changed. But the economy has changed in ways that have kept poverty high. Labor-saving technological changes, globalization, the erosion of union membership, changing public policies have all contributed to wage stagnation for the bottom half of workers.”

Danziger notes that, “On the one hand, there has been remarkable technological progress that enhances our productivity. My laptop has more computer capacity than I had available writing my dissertation on a main-frame computer.”

“But,” he goes on to say, “That same technology has negative effects on workers that we don’t usually think about. The gains of economic growth are no longer widely shared, as they were in the quarter century after World War II; now, they flow mainly to the economic elite.”

Ironically, technological advances that have fed this increased inequality also provide scholars with both richer data and the computer capacity that allows them to address important questions about the causes and consequences of poverty.

“It was once very difficult to study how poverty is passed on from generation to generation,” Danziger says. “One of the key data advances, the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, was started in the late 1960s by Jim Morgan and his colleagues at ISR [U-M’s Institute for Social Research]. It continues and is now gathering data from the grandchildren of the original study participants. Researchers can now examine how poverty and affluence are transmitted from generation to generation.”

On poverty, policy, and people Sheldon Danziger’s lasting legacy “The economy has failed the poor in recent decades. No one in the early 1970s would have thought that by 2013, inflation-adjusted earnings would be so little changed.”

But policymakers today are much less interested in research findings than they were four decades ago, Danziger believes. He illustrates this point with an assessment of the government’s poor performance in modernizing the country’s crumbling infrastructure. Views about infrastructure are certainly not polarized as are views about poverty. Yet, despite much evidence from engineers about the need for repairs, Congress has not taken up the president’s call for increased infrastructure spending.

“At a time when the unemployment rate is high, when workers can be hired without driving up inflation, and with the federal government able to borrow at a zero interest rate, this would be a policy that would increase productivity and easily pass a benefit-cost test. Yet, many in Congress reject any proposals that require more spending,” Danziger says. “We also have antipoverty policies that would pass a benefit-cost test. But, if we can’t get action on repairing bridges how can we get action on providing more for the poor and their children?”

Despite the current gloomy situation, Danziger believes that “Poverty researchers should keep evaluating new ideas. At some point, when the political environment is more open to policy reforms, they can pull the promising practices off their shelves.”

Danziger has done much during his career to ensure that welltrained researchers, from diverse backgrounds and from diverse disciplines, are out there, continuing to conduct high-quality studies.

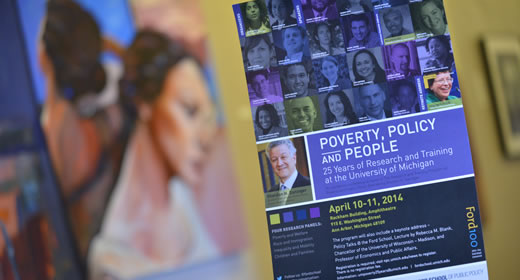

Twenty-five years ago he founded a post-doctoral research and training program on poverty and policy. Later, he was founding co-director of the National Poverty Center, housed at the Ford School, which expanded that work.

At a Ford School conference this April, dozens of Danziger’s former students and colleagues celebrated and explored the impact—scholarly, professional, and personal—of his teaching and mentoring.

“I benefited from excellent mentoring when I was a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Wisconsin– Madison,” Danziger says, “so when I came to Michigan in 1988, I wanted to use teaching as a way to mentor doctoral students and postdoctoral fellows. I was fortunate to be able to co-teach a seminar with my colleague Mary Corcoran that trained a new generation of poverty researchers, but also facilitated my own research agenda by fostering many collaborations with participants.”

For Danziger, the students he worked with are as central to his legacy as his prodigious scholarly achievements. Most are faculty members themselves, now training and inspiring their students at colleges and universities around the world. Others are employed at foundations, think tanks, research firms, non-profits, and government agencies.

Perhaps, Danziger hopes, the time will come again when policymakers see researchers as partners. If and when that happens, his former students will be ready.

--Story by Jeff Mortimer

Below is a formatted version of this article from State & Hill, the magazine of the Ford School. View the entire Fall 2014 State & Hill here.