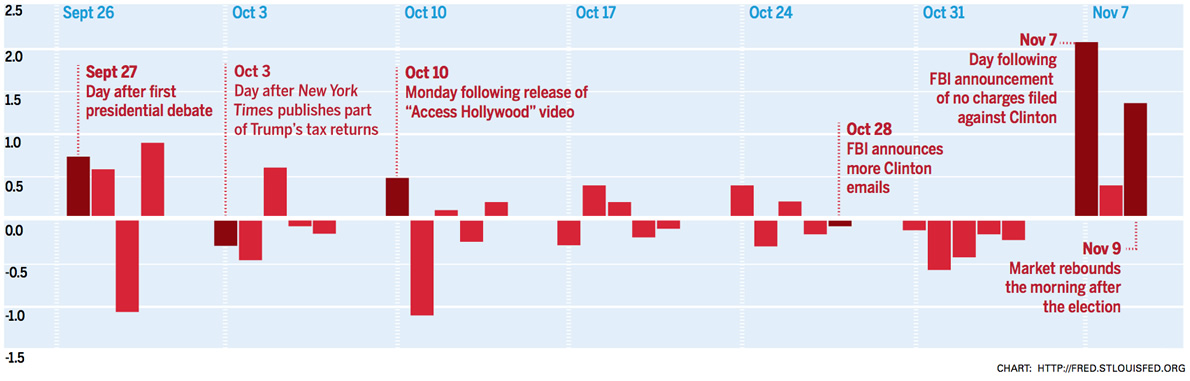

As Trump gained strength on election night, the prices of Clinton securities on political betting markets fell sharply. By midnight, stock market futures for the Dow Jones Industrial Index had fallen by 4 percent. Both movements reflected what traders had previously expressed in markets—their belief that a Trump presidency would be a drag on the economy. Yet after the opening bell the following morning, stocks began to rebound.

Pundits and economists were generally puzzled by this. The day after the election, many Ford School students, and Justin Wolfers himself, were visibly shaken.

On October 20th, the Brookings Institution had released what would quickly become a widely discussed paper. Written by Wolfers of the Ford School and Eric Zitzewitz (of Dartmouth), it showed how financial traders reacted to changes in the perceived likelihood of a Clinton presidency during what seemed like the critical turning point in the election—the first Presidential debate.

Almost immediately, newspapers, magazines, and television outlets across the world covered the research.

Stateside, FiveThirtyEight asked if investors were “#withher?” The Atlantic argued debates still matter. And the Wall Street Journal suggested “a great trading opportunity.” Overseas, London’s Financial Times discussed prediction markets as a window into the economic effects of politics. The Sydney Morning Herald noted “parallels in Australia.” And citations and media mentions have continued to pour in.

How did it start?

|

|

On September 26th, before the 9 p.m. (ET) start of the first presidential debate between Clinton and Trump, most commentators felt Clinton had a slight edge. National polls had Clinton leading by several percentage points. “Data nerds” and “quants” agreed as well: Nate Silver of FiveThirtyEight calculated Clinton had a 55 percent chance of winning. Traders on one betting market, BetFair, gave Clinton a 63 percent chance of winning the election.

Wolfers had long been an observer of political prediction markets, where bet-like securities for each candidate are bought and sold. Each of these securities pay out either $1 or nothing after the election, depending on the winner. Prices of securities reflect the expected payout, meaning if the likelihood of a Clinton presidency is thought to be 63 percent, Clinton securities trade for 63 cents each.

As the debate progressed, Wolfers watched for changes in prediction market securities prices. At first, they held steady. But after an opening appeal that drew mixed-remarks from pundits, Clinton rallied, responding with increasingly persuasive points and rebuttals. Wolfers, with an iPad tab on the political betting markets, watched prices for a Clinton presidency move sharply higher, reflecting increasing belief in the likelihood of a Clinton presidency.

|

|

Interestingly, betting markets weren’t the only financial markets to react. Many of the most highly traded assets on global markets—S&P futures, government bonds, oil, and foreign currencies—changed prices overnight. Slight changes in prices during after-hours trading are normal. Not, however, to the extent observed the night of the first debate. The U.S. Dollar to Mexican Peso exchange rate fell by nearly two percentage points, a massive decline compared to the typical overnight adjustment. Wolfers called this price adjustment “a statistically significant move, not one caused by mere chance.”

The coincident shift in political prediction and financial markets revealed traders’ expectations: according to Wolfers’ calculations, the market reaction implied the S&P would be worth “12 percent more under a President Clinton.”

It wasn’t the first time financial markets had moved in response to presidential campaign events.

Wolfers, who likes to track elections through prediction markets, described watching a similar reaction on election day in 2004. That afternoon, exit polls unexpectedly showed democratic hopeful John Kerry leading in Iowa. U.S. stock markets, which had opened higher, quickly fell. Traders dumped pharmaceutical and energy stocks, gold, and oil—all industries and assets that would be particularly affected by Kerry’s policy promises. Of course, the early polls were wrong: President Bush would win 286 Electoral College votes. And futures markets quickly corrected the earlier decline.

Then, why was Wolfers’ new research so widely covered? One explanation is that it highlights what we thought were two departures from historical trends.

“In almost every case back to 1880,” writes Wolfers, “equity markets have risen on the news that Republicans win elections and fallen when Democrats win.” In recent elections, Republican presidential candidates have promised lower taxes, which boost corporate profits and raise stock prices.

|

|

Despite his policy idiosyncrasies, Trump seemed to fit this mold. Yet markets broke with the past anyway. The Economist captured it well in this title, “No Trump! For once, Wall Street does not favour the Republican candidate.”

The second departure is that the market’s view of a Trump presidency was drastically different from its view of a Clinton presidency. “A twelve percent difference is large both in absolute terms, and relative to how previous political shocks have moved the market,” wrote Wolfers.

Yet what happened on election night, and the morning after, muddies what Wolfers’ research tells us about the economy under President-elect Trump. Traders that night were acting as Wolfers predicted, dumping stock market futures as Trump’s win became more likely. By the early morning, however, markets were up, and traders had seemingly abandoned their dire predictions of a Trump economy.

This shift left the two economists pondering what happened.

Wolfers, in a New York Times Upshot column, mentioned a number of possibilities—Trump’s victory speech, in which he emphasized infrastructure spending; news that Republicans would likely continue to hold the House and Senate; a reduction in uncertainty; and the theory preferred by Zitzewitz, his co-author, that the faulty prediction of futures traders amounted to a polling error that was corrected when European markets opened around 2 a.m. (ET) on Wednesday morning.

Wolfers’ own view was different, and perhaps, simpler: investors failed to predict their own feelings about a President-elect Trump. There was “a failure of imagination,” writes Wolfers.

Wolfers’ new research isn’t a crystal ball, but it gives us another way to evaluate presidential candidates, and other major political and policy shifts—the lens of markets.

By Anthony Cozart for State & Hill, the magazine of the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy

Below is a formatted version of this article from State & Hill, the magazine of the Ford School. View the entire Fall 2016 State & Hill here.