After months of studying the cost of auto insurance, Joshua Rivera (MPP ’17) finally had the data he needed to see how much Michiganders spend to keep their vehicles insured.

What he found shocked him.

"When I saw that 97% of the zip codes would be considered unaffordable, I thought I messed up," said Rivera, senior data and policy advisor at the University of Michigan’s Poverty Solutions initiative.

He ran the analysis again and reached the same conclusion: in 97% of Michigan zip codes, the average auto insurance rate accounted for more than 2% of the median income, which the U.S. Treasury Department’s Federal Insurance Office deems “unaffordable.”

That finding proved vital in reforming Michigan’s auto insurance system. In March, Poverty Solutions published a policy brief on the link between auto insurance and economic mobility, based on research by Patrick Cooney (MPP ’11), assistant director of Poverty Solutions’ Detroit Partnership on Economic Mobility; research consultant Elizabeth Phillips; and Rivera.

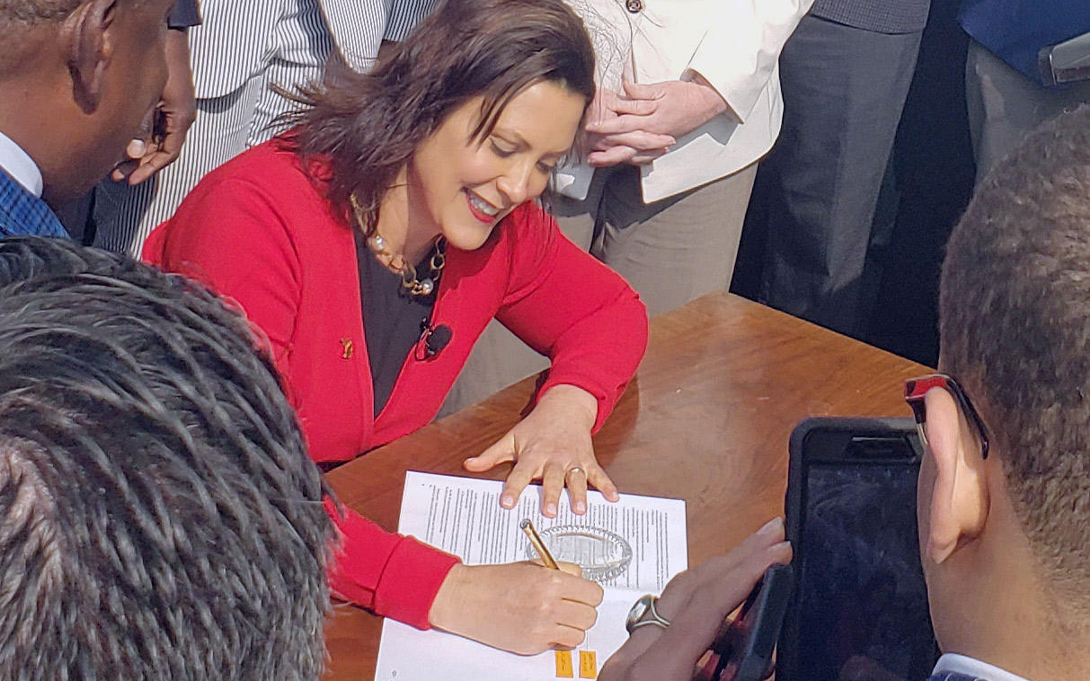

Two months later, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer signed into law historic auto insurance reform measures. The legislation included many of Poverty Solutions’ recommendations, such as eliminating automatic unlimited personal injury protection coverage, imposing fee limits on medical care related to personal injury accidents, and restricting the use of non-driving factors like credit score and zip code to determine auto insurance rates.

It’s uncommon to see research so quickly translate to a change in state law, said Poverty Solutions faculty director H. Luke Shaefer, an associate professor of social work and public policy.

“I think it had the impact it did because it was the right type of research product, at the right time,” Shaefer said. “It looked at the issue from a different angle than other work had, and I like to think it provided some concrete, non-partisan policy recommendations—recommendations that straddled party lines.”

Auto insurance as an economic issue

Poverty Solutions’ interest in auto insurance came naturally from the university-wide research initiative’s mission to work with community partners to find new ways to prevent and alleviate poverty.

As Poverty Solutions began in 2018 to evaluate a job training program in Detroit, the cost of auto insurance kept coming up as a barrier that prevented people from owning a vehicle or driving it legally—thus limiting their job options.

“We didn’t look for it; we didn’t expect it,” Shaefer said. “But it came up over and over again as a major barrier to getting to jobs, schools, health appointments—all the things people need to live healthy and productive lives. While I had never thought of it as such, it is a poverty issue in Michigan.”

The work eventually led Poverty Solutions staff to data from The Zebra, an auto insurance rate comparison company that tracks average rates by zip code.

The average annual auto insurance premium for Detroiters is $5,414, roughly double the statewide average, which already is the most expensive in the country.

More than one-third of Detroit residents live at or below the poverty line, and for a family of four with an income right at the poverty line, the average cost of car insurance in Detroit would take up 22% of their annual income.

“What was striking was that you could see the problem starting to spread throughout the state, particularly in Southeast Michigan,” Rivera said. “While there was a heavy concentration of unaffordability in the City of Detroit, it was creeping over time to the suburbs. More people had a stake in whether or not reform happened.”

Growing demand for reform

It didn’t take long for Poverty Solutions’ findings to garner national attention.

Media coverage highlighted the reasons auto insurance was unaffordable for so many Michigan households, and lawmakers reviewed Poverty Solutions’ analysis to inform their approach to reform, Rivera said.

Whitmer cited Poverty Solutions’ work in a mandate in early May for the state’s Department of Insurance and Financial Services to review how auto insurance rates are set and strengthen consumer protections.

That same day, Rivera testified about Michigan’s auto insurance policies before the U.S. House Financial Services subcommittee. The high cost of auto insurance in Michigan served as a cautionary tale in the national debate about the federal government’s role in regulating the industry, Rivera said.

Rivera testifying before the U.S. House Financial Services Committee’s Oversight and Investigations Subcommittee

“The reason our report was so helpful in this discussion was because it represented an outside interest in a debate in which there are millions of dollars at stake,” Rivera said.

Measuring impact

After weeks of debate, a bill to reform Michigan’s auto insurance law passed with bipartisan support. Still, critics question whether the changes will translate to a meaningful reduction in costs for consumers as promised.

Rate reductions for personal injury protection are guaranteed and drivers will have the option to carry varying levels of coverage, which also could save them money. But personal injury protection accounts for only a portion of the cost of auto insurance, and there’s no requirement for insurers to reduce charges overall.

The new law also prohibits insurance companies from using non-driving factors like gender, marital status, home ownership, educational level, occupation, credit score or zip code to set their rates. However, insurers can still set rates based on an “insurance score” that incorporates credit and by “territory,” which could be an area as small as a census tract and contribute to redlining.

With some aspects of the reform yet to be defined by regulators, it’s too soon to estimate how the new law will impact the overall affordability of auto insurance in Michigan, Rivera said.

Shaefer said Poverty Solutions will continue to monitor the issue, assess the impact of the reform, and think about other ways to make auto insurance affordable in Michigan.

“One bill isn’t the end of work on a policy area,” Rivera said. “It’s the beginning of a conversation on how to do better.”

Below is a printed version of this edition of State & Hill, the magazine of the Ford School. View previous editions.