It has been a topic that many Black parents in the United States have discussed with their children in recent decades—staying safe from harm or being killed by law enforcement.

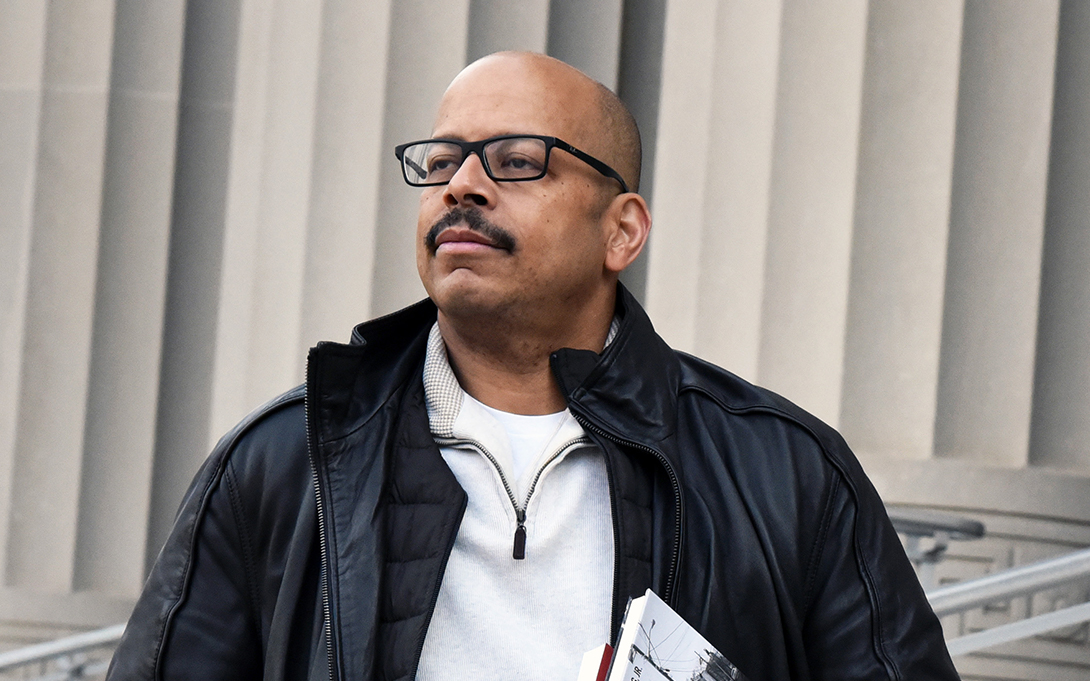

But in recent months, the conversation now extends to Black youths being killed in regular situations by white citizens, said Alford Young Jr., a University of Michigan sociologist, and Ford School courtesy professor, who has conducted research on African Americans. He puts into context what must happen to eliminate these deadly encounters, noting that any change will involve multiple agents and won’t happen overnight.

Why is this moment different for Black children and Black parents?

There have historically been conversations in the home with Black children, in particular Black boys, about how you handle yourself in difficult situations, whether it’s with the police, whether it’s in threatening or dangerous situations. Now the concern is being out in public and how you might handle yourself in everyday business on the street corner, in neighborhoods and in communities. And it’s almost as if there is no real conversation to be had because how do you tell people to be prepared for violence just because you’re in a public space? I think there is a desire for conversation. There is a quest to figure out what conversations can be had.

Some of this seems to be a racist or misconception by some non-minorities about Black men being dangerous. What might change this perception?

The changing of perceptions is twofold. On the one hand, it’s about young men in the public that sometimes foster images of concern or anxiety. Men are sometimes aggressive. Black men or young boys can be expressive and that causes consternation or concern among the broader public.

But they’re being different isn’t all that’s in play. We’ve seen Black men face threats or violence just being in neighborhoods. It’s not about the aggressive or hostile behavior. It’s about going about exercising, watching birds in a park. Doing things that are no way consistent with the age-old notion that, “You can’t be too expressive. You can’t be too assertive.”

And so the perception in large part is in the hands of other people. It’s people outside the categories of Black boys, Black men, Black people who need to take stock in how and why they think about these people as they do. What is limiting one’s capacity to recognize the humanity of these people? The broader public has to understand that there is work to be done on its part. It’s not just simply waiting for people to behave differently.

Earlier, you mentioned figuring out how to start the conversation. How does this happen?

My own view is that social institutions are the perfect place for these conversations to happen. They have to happen in schools; I mean early education to higher education. If our objective in schools is to train people to be functional in society, they have to be responsive to all kinds of people in society. So it means learning how to engage with people different from themselves.

Other institutions like churches—places where notions of community loom large. What kind of community are we inviting to these churches? Pastors and church leaders are perfectly situated to convene those conversations, to make them happen, to explore them.

And the last site—and perhaps the more challenging—is government itself. Aside from talking about issues of individual liberties and rights, what about communities’ responsibilities of engaging other people? Are those conversations happening in Congress, in state legislatures? So much of the conversation is about protecting the individual. Some of it needs to be how to protect and serve healthy communities—and means talking about obligations to other people.

With multiple agents involved, how likely will we see change—seeing fewer deaths caused by white gun owners?

I think that critical agents pushing the conversation now means that in decades to come change will happen. I don’t expect overnight change. I’ve never expected overnight change when it comes to race, race relations, and the health and well-being of African Americans, but you start incrementally to have change over time.

This interview was prepared by Jared Wadley of Michigan News.