The University of Michigan invited Professor Barry Rabe to address the 89th Honors Convocation of the University, an event that celebrates and recognizes outstanding academic achievement by undergraduates. The theme of this year's Convocation: "Making a Difference in the World: Do We Need to Travel to Understand Global Affairs?" Rabe was named a Thurnau Professor in 2011 in recognition of his teaching excellence and commitment to enhancing undergraduate academic opportunities. Here is the speech he delivered to a crowd of 3,300 at Hill Auditorium on March 18, 2012.

Some 12 years ago, this marvelous auditorium was similarly packed. There was another celebration—and a bit of tension. Standing where I am today was Dr. Henry Kissinger. Then, as now, a controversial figure. One of the most influential 20th century Secretaries of State. As he began, so did heckling. A rather unflattering banner was unfurled from the balcony. (I can only hope that history does not repeat itself today.)

But Kissinger kept going and gave what I still consider to be the best speech I have ever heard him deliver. He spoke about the challenges of American foreign policy between 1974 and '76. And he spoke with deep emotion about the president he served during that period: The Accidental President. And yet a president who, borrowing from today's theme, devoted six decades of public service to "making a difference in the world."

That president, Gerald R. Ford, was seated right behind Kissinger, about where Provost Hanlon sits now. The occasion was the transformation of the U-M School of Public Policy into the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy. It was a grand day in every possible way.

But as I sat there in the second row, I realized I knew very little about Gerald Ford. I finished high school and began college during his presidency. I had some aspiration to "make a difference in the world." And as the first member of my family to attend college, I surely was not giving thought to "traveling to understand global affairs." The farthest I got from my college campus in Wisconsin was Stratford, Ontario to see Hamlet.

It is, I think, quite safe to say that in the years he spent at this university in the 1930s—and have we ever had a president who so loved his alma mater as Gerald Ford??—the very idea of studying global affairs, much less traveling to understand them would have seemed absurd.

Jerry Ford was a very busy guy in Ann Arbor. Four years of varsity football, in an era with no scholarships. A full academic load, with one of the strongest academic records of any 20th century American president. (Angell Scholar material except for his French language classes.) He worked two jobs, including waiting tables at the University hospital. He donated blood every second month in exchange for $25 that helped ends meet.

Travel to understand global affairs? The farthest he travelled from this campus involved two trips to Minnesota to secure possession of the Little Brown Jug. Then an all-star game in San Francisco. In his memoirs, he readily admits he had little or no interest in global affairs and thought America's role in the world should be minimal. He wanted to practice law in Grand Rapids.

|

|

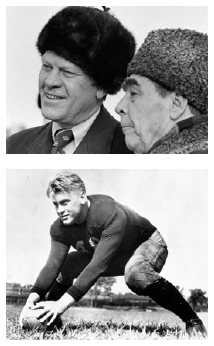

Top: President Ford dons a Russian wool cap upon his arrival in the Soviet Union in 1974, shown here with Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev at Vozdvizhenka Airport, Vladivostok. |

But then Gerald Ford got to experience global affairs, via the Navy in World War II. Lieutenant Gerald Ford saw heavy action in the Pacific, returned to Grand Rapids and was appalled to see that his Congressman was championing the cause of (literally) "No, no, no." No to any America postwar engagement in global affairs; "not a penny for the Marshall Plan."

With that, Ford abandoned his law practice. He embraced the positions of Michigan Republican Senator Arthur Vandenberg (class of 1901) on these issues, defeated the five-term incumbent from his own party, and won that seat. The near-exclusive focus of the Ford campaign was active and constructive American engagement in global affairs.

From there, Gerald Ford never looked back. He travelled—relentlessly—as a member of Congress and as president. These were not junkets. From all that we know from historians, these were designed to gain an understanding of global affairs. To talk, but also to listen. And also to give people a little different view of America. This was, after all, the president who banished the playing of "Hail to the Chief" in favor of "The Victors."

So Gerald Ford spent more days out of the U.S. during his relatively short presidency than any of his predecessors. Went everywhere, talked to everyone, listened to anyone with ideas from direct experience outside U.S. boundaries. Two quick stories.

First, Ford presided over the last days of American involvement in the Vietnam War. A truly agonizing final set of weeks. The Economist asked on its cover: "Is America Fading?" Surveys showed that the only country Americans would agree to defend if attacked was Canada.

Twelve days after the evacuation of the last American solider, an American merchant vessel (the Mayaguez) was seized off the coast of Cambodia. Details were sketchy but how to respond? Most of President Ford's advisors proposed massive mainland bombing strikes, with B-52s. What better way to project American power? As the meeting went forward, 28-year old White House photographer, David Kennerly, piped up. President Ford had allowed—encouraged—him to make one of the last trips into Vietnam and Cambodia.

Kennerly was only at this meeting to take pictures. But could not contain himself. He noted that, from his recent observations, Cambodia had no functioning government. We had no idea where the hostages were. He said a massive bombing campaign was absurd. In his memoirs, Gerald Ford said, "I thought what Kennerly had said made a lot of sense." Ford took the first-hand observation, reversed his top aides (including Kissinger), and pursued a more nuanced approach. The hostages were released within days.

Jerry Ford played both defense and offense at Michigan. But he preferred playing center on offense. So true with the rest of his presidency. He believed, relentlessly, that as president he could establish strong links with national leaders and find common cause. His presidency was a flurry of international engagements, even though this hurt him in both securing the Republican nomination against Ronald Reagan and in the general election against Jimmy Carter.

Perhaps his role in Europe was his finest hour. Ford actively worked with every European leader he could find and built an understanding of the humanitarian provisions of the proposed Helsinki Accords. This was relentless personal diplomacy—and not on his home field. Ford then sealed the deal and followed with visits to places no president had ever been before, including Poland, Romania, and Yugoslavia. Historians today acknowledge that these controversial accords helped open up Eastern Europe.

Even in an era of instant communication and social media, I believe that Gerald Ford would answer this question of the need for travel to understand global affairs in the affirmative. That said, he might also offer the following advice: you must travel. But prepare in advance and do not be afraid to listen. And, perhaps, show them a little different side of your American experience. What better way to do that than always have ready on your iPod a sterling rendition of "The Victors."

Below is a formatted version of this article from State & Hill, the magazine of the Ford School. View the entire Spring 2012 State & Hill here.

Photo credit: Gerald R. Ford Library