In 2010, Carl Simon and George Kaplan received funding from the National Institutes of Health to build an interdisciplinary network of scientists to look at a very important problem, socioeconomic health disparities, viewed as a complex system.

“We had held a conference at U-M to talk about complex systems methodologies and health, and some sessions were standing room only, so we knew there was interest,” says Simon. “But while complex systems methods had been used successfully to model the spread of contagious diseases, we wanted to see whether they might help to illuminate other health issues—particularly things like depression, diabetes, and health concerns related to socioeconomic status.”

For the next four years, Simon and colleagues in the highly interdisciplinary “Network on Inequality, Complexity, and Health” did just that—meeting regularly to discuss shared interests. The fruits of their interdisciplinary approach will appear in Growing Inequality: Bridging Complex Systems, Population Health, and Health Disparities (Westphalia Press, 2016).

In Chapter 3, Simon and his coauthors, who include Tom Boyce of the University of California, Berkeley; Jeanne Brooks-Gunn of Columbia University Teachers College; and Steve Suomi of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; write that, “In virtually every human society on Earth, the incidences of biomedical disorders, psychiatric conditions, and traumatic injuries within childhood populations increase linearly as socioeconomic status decreases. The association between socioeconomic status and child health…is one of the most powerfully predictive associations in contemporary epidemiology.”

The piece explores how inequalities—in the form of hierarchies—can impact communities in the short- and long-term, outlining a series of related research initiatives by network faculty.

Simon’s contribution—a simulation based on data collected about classroom interactions and hierarchies—explores how teachers might intervene to reduce inequality. “When things go awry in a classroom, there are often two to three kids at the top and everyone else at the bottom,” says Simon, “there’s a big spread.”

Using a complex systems approach, Simon and his colleagues found that a few factors really mattered: class size, the value of the reward children were competing for, and the chances that an underdog might win.

“It turns out that if teachers reduce the value of the reward—from a pizza party to a sticker—and organize competitions that give everyone a chance, even kids who didn’t do so well last time, inequality can be reduced,” says Simon. Competitions that always focus on dodgeball, for example, will always reward kids with the best large motor skills. Teachers might intersperse such competitions with others that reward different talents.

In the same chapter, network colleague Steve Suomi contributes findings from long-term studies of rhesus monkey colonies, which naturally develop social hierarchies. Low-ranking females, he reports, are more likely to be the targets of physical aggression, to have lower levels of play and exploration, and to be physically displaced from group activities. In addition to these social and psychological difference, veterinary records show that low-ranking females “also require more veterinary treatments for injury and wounds…have higher rates of infection, and have higher rates of gastro-intestinal disorders.”

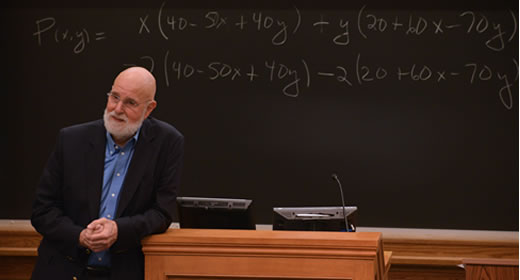

Carl P. Simon is professor of mathematics, complex systems and public policy at the University of Michigan. He was the founding director of the U-M Center for the Study of Complex Systems (1999-2009) and current directs U-M's Science, Technology, and Public Policy (STPP) program. His research interests center around the theory and applications of dynamical systems.