The last place David Thacher expected to uncover a largely overlooked policing philosophy—one highly relevant to today’s police reform discussions—was from a man best known as a landscape architect in the late 19th century.

In fact, he kind of stumbled into it.

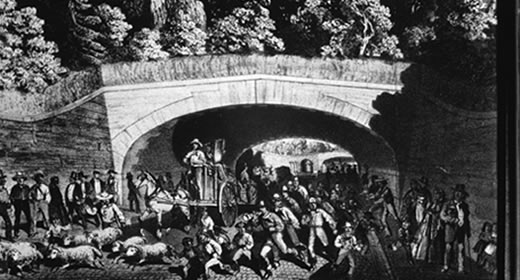

During the process of planning for his course on public spaces, Thacher began examining the work of Frederick Law Olmsted, co-designer of New York’s Central Park. While he focused initially on Olmsted’s theories on shared public spaces, Thacher discovered that Olmsted had also overseen Central Park’s management intermittently over the course of two decades. This responsibility included managing the Central Park Police.

Thacher, an associate professor of public policy and urban planning with a longstanding interest in criminal justice and policing policy, was intrigued.

As he began digging into Olmsted’s work he uncovered detailed ideas on policing that were vastly different from what his criminal justice contemporaries were discussing. Of particular interest to Thacher was Olmsted’s unique approach to policing public spaces and “order maintenance,” the management of small offenses that can be disruptive to communities.

Thacher discussed the rich archival material he was finding with Samuel Walker, a police historian at the University of Nebraska-Omaha, who confirmed that the line of inquiry was unique. While social historians had documented Olmsted’s role with the Central Park Police, his work – which delved far more deeply into order maintenance work than anyone else in American policing had at the time – hadn’t really been examined from a criminal justice or legal perspective.

So Thacher dug deeper. Much deeper, actually, than he ever anticipated.

“When I set out, I thought this might take a few months of research and be a relatively short, easy piece,” said Thacher. It turned into a 20,000-plus-word journal article, published in the Law and History Review in August, that he worked on intermittently for several years.

The research

While small order maintenance offences accounted for the majority of police work in the 19th century, detailed accounts or records of what this looked like in practice are lacking.

Olmsted, however, kept meticulous and copious notes. And because of his prominent status as one of America’s most famous landscape architects, much of that work has been preserved and anthologized. Although the majority of Olmsted’s catalogued writings focus on urban design and landscape architecture, his policing notes were well preserved, too. Additionally, since he oversaw a public agency, official records and documents were maintained and still exist.

Thacher studied it all: Volumes of Olmsted’s writings; microfilm slides of handwritten manuscripts, memos, and letters; annual reports; Central Park Board of Commissioners meeting minutes; general orders written to his police force; newspaper articles; and journal entries documenting his interactions with city officials.

While daunting at times, the trove of available content was exciting to Thacher.

“Examining Olmsted was actually easier than a lot of historical research is,” he said. “Because he’s a famous guy, his writings are rather accessible. Historians have captured a lot of his work and the Library of Congress has original manuscripts [of his] on microfilm.”

From the material, a relatively detailed picture of 19th century park police work emerged, as did an ambitious concept of the police role—one that is radically different from the one we’ve inherited.

An educative model of policing

Olmsted took his role managing the park police very seriously, says Thacher. He thought deeply about the distinctive nature and requirements of the urban public realm and the task of “defining and enforcing standards of behavior that would allow thousands of park visitors to coexist.”

He was chiefly concerned with the proper policing of actions that, on their own, may have been of little consequence, but if committed by many, would erode the quality of the shared urban environment.

Thacher notes several such offenses, including park visitors “helping themselves to flower bulbs and birds’ nests, wearing down the turf in heavily traveled areas, spitting tobacco, leaving rubbish on the walkways, and carving their initials into park benches and buildings.”

Olmsted’s solution to this order maintenance dilemma was to advocate for an educative model of policing in which the mission of the park police was fundamentally instructional.

“It was ‘to aid, instruct, and restrain honest but often inconsiderate visitors in their use of the Park,’” Thacher writes. The threat of arrest and traditional court-backed sanctions, Olmsted held, should only “lurk in the background,” rarely mobilized.

Olmsted’s educative archetype was a radical departure from the prevailing theory governing 19th century policing, 'the deterrence model,' in which the main task of the police was to restrain malice by threatening the malicious with punishment.

Implications for today

More than 150 years later, the deterrence model of policing still prevails. And the order maintenance role in policing has become synonymous with “broken windows policing,” commonly understood (some would say misunderstood) as the use of public order rules as an excuse to question, search, detain, and punish anyone an officer happens to find suspicious.

Contemporary calls for police reform often center on ending the broken windows approach that activists claim is at the center of criminal justice disparities.

Thacher, who has written about broken windows policing frequently, thinks Olmsted’s educative framework offers a promising alternative.

“I think we’ve lost a sense of the real importance and real nature of this public order task,” he said. “[Olmsted] provides some sense of an alternative. His acknowledgement that other forms of regulation and social control — aside from arrest and punishment — could be applied to deal with more menial problems and offenses is important for rethinking the order maintenance role today.”

David Thacher is an associate professor of public policy and urban planning at the University of Michigan. His research focuses on criminal justice policy, including order maintenance policing, the local police role in homeland security, community policing reform, the distribution of safety and security, and prisoner re-entry. Outside of criminal justice, he has also conducted research on urban planning and on adoption policy.

--Story by Paul Gully (MPP '16)