“They lost their voices, they lost control of their lives, they lost their home,” Hal Kohn says of his grandparents. “They fled from Germany to Amsterdam, but Hitler invaded the Netherlands and they were deported to Sobibór and murdered upon arrival.”

Hal’s wife Carol draws a line from 1940s Europe to the United States now. “While the situation here is less extreme, many people in the U.S. today are denied the right to live without prejudice and restrictions. We say all people are created equal here, but some have no voice in society. They have been denied their rights or their ability to have successful lives.”

Alarmed by this state of affairs, the Kohns sought the best way to address the denial of social justice in the United States. “It was beyond our ability as individuals,” says Carol. “So, we looked for an organization with that infrastructure and passion to do meaningful research and create programs that would have an impact.”

The Kohns chose U-M’s Gerald R. Ford School for Public Policy as that organization. A significant gift from the Kohn Charitable Trust will establish a new professorship of social justice and social policy at Ford. The gift will support a faculty member who, through scholarly and applied research, is “giving a voice to the disadvantaged in society.”

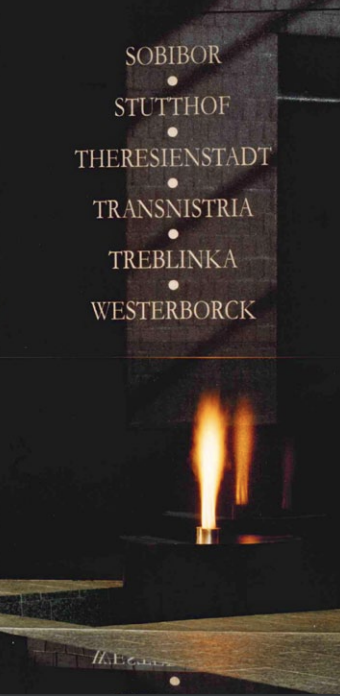

The Holocaust Memorial Center in Farmington Hills, Michigan lights this memorial flame in honor and memory of the over 6 million Jews who perished in the Holocaust. Photo courtesy of the Holocaust Memorial Center

Hermann Kohn, born in 1871 in Lülsfeld, Germany, a small town between Frankfurt and Nuremberg, and Amalie Schwab, born two years later in Rimpar, 20 miles to the west, would not have seemed disadvantaged. As a young man, Hermann became successful in the sale of hand tools and machinery in nearby Gerolzhofen. He married Amalie in 1900, and they had two children, a daughter, Rosl, in 1901, and a son, Karl, in 1907. In 1927, Rosl married Ludwig Löwenthal, whose political views were unpopular with the National Socialists then gaining power in Germany. The Löwenthals fled to Amsterdam in 1933. Thereafter, conditions in Germany deteriorated. In 1936, Hermann arranged for Karl to emigrate to the United States. His parents hoped to follow.

According to Beit Hatfutsot, the Museum of the Jewish People, on November 9, 1938, known to history as Kristallnacht, Jewish homes in Gerolzhofen were broken into and searched. Personal property was destroyed, anti-Semitic slogans were painted on houses and tombstones were overturned in the Jewish cemetery. A week later, the town’s Jewish males were shipped to Dachau. Hermann Kohn managed to avoid this fate; he and Amalie soon followed their daughter to Amsterdam. In May 1940, however, Hitler invaded the Netherlands. In the spring of 1943, the Kohns and the Löwenthals were arrested. The Löwenthals were sent to Theresienstadt in Czechoslovakia and the Kohns via Westerbork to Sobibór in eastern Poland, where they died within days. Hermann was 73. Amalie was 70.

In America, Karl Kohn married another refugee, Martha Sternberg, in 1937 and settled in the Washington Heights neighborhood of New York City. Like his father, Karl took up the hardware business. “We were fortunate,” Hal says today of himself and his two sisters. (Rosl Löwenthal survived the Shoah, though her husband and son did not.) “My parents made us their number one priority.” Part of Hal Kohn’s good fortune was being able to attend the University of Michigan, in the early 1960s. “It was an interesting time to be on campus,” he recalls, “civil rights and Vietnam galvanized our attention. America was really grappling with its history. Because of my grandparents, I believed these were meaningful questions. It was a formative period of my life. I was proud of U-M’s tradition of social justice, and I have remained so.”

Hal Kohn received his PhD in Chemistry from the Pennsylvania State University in 1971. Following postdoctoral study at Columbia University and a faculty appointment at the University of Houston, he came to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1999. Two themes defined his research career: elaboration of the mechanism of action of clinical agents, that is, the exact biochemical interaction by which a drug substance produces its pharmacological effect; and the discovery and evaluation of new therapeutic agents. Hal retired in 2015. His and Carol’s quest for an institution to support in the pursuit of social justice intensified.

The Ford School is having a major impact, addressing social justice and giving a voice to people at the margins of society. Creating a professorship at Ford will empower a researcher to explore boldly, at liberty to follow their vision.

In 2017, they contacted the University of Michigan to discuss their vision. They learned about Poverty Solutions, an interdisciplinary program launched by U-M President Mark Schlissel and housed at the Ford School, under the direction of Associate Professor Luke Shaefer. The initiative seeks to address poverty through partnerships with community groups and policy leaders. “We knew immediately that we wanted to give to the Ford School,” Hal says. “Ford and President Schlissel are committed to the values of Poverty Solutions. We were struck by the School’s partnerships with the state and the city of Detroit. The Ford School is having a major impact, addressing social justice and giving a voice to people at the margins of society. Creating a professorship at Ford will empower a researcher to explore boldly, at liberty to follow their vision. We want to engage and keep the best at Michigan.”

“At the time, my grandparents’ passing was noted only by their names on a ledger. That always stuck with me. But now, they will no longer be silent. Their voices and the voices of many others will be heard. We will benefit from that wisdom and experience, through the efforts of those at the Ford School. It gives us tremendous happiness.”

The elder Kohns’ voices are already being heard in a very twenty-first century way. They have made their social media debut. “We were scrolling through Ford’s Facebook page,” Carol says, “and Hermann’s and Amalie’s pictures came up. It meant so much to us that they were there for everyone to see.”

Hal sums up with an amusing and telling analogy from the discipline in which he made his career. “I see the world through the lens of chemistry,” he says. “So, I was struck by the name Poverty Solutions. In a solution, different compounds dissolve, then interact and are transformed. The Ford School puts people together—especially in partnerships across the state—and they interact, and the outcome is the betterment of society, giving all people a voice and a path.”

—Story by David Pratt

More in State & Hill

Below, find the full, formatted Winter 2019 edition of State & Hill. Click here to view the entire Winter 2019 State & Hill Magazine edition.