Between mid-April and early August, Kazu Shibuya (MPP ’88) had already made nine trips from Tokyo to Washington D.C. and he was getting ready for his tenth. It is what his role as deputy minister and leading negotiator for the government of Japan calls for while his country and the United States are in the thick of negotiations to craft a bilateral trade agreement.

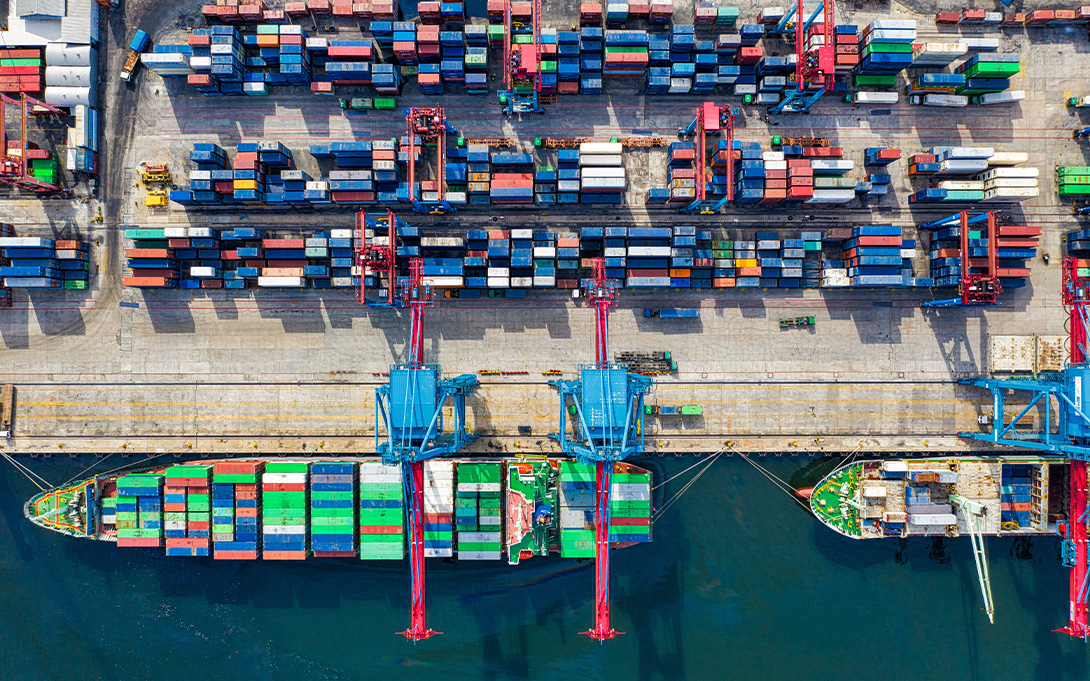

There is a lot at stake for the two economies. Japan is the fourth-largest U.S. trade partner, behind Mexico, Canada, and China. In 2018, U.S. exports to Japan accounted for over $120 billion while U.S. imports totaled nearly $180 billion. Foreign direct investment is also important for both countries. The United States holds significant investments in the Japanese finance and insurance sector while Japanese investment in U.S. manufacturing supports thousands of domestic jobs, especially in the auto industry, according to the Congressional Research Service.

Although Shibuya comes to the table as a seasoned expert in trade negotiations, his path has been unusual and it was not at all what he had in mind when he signed up for a degree in public policy at the Institute of Public Policy Studies, or IPPS, (the predecessor to the Ford School).

Shibuya applied to IPPS from the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport, where he had worked for three years after earning a law degree from Tokyo University. He had backing from a Japanese government program for graduate studies abroad that has sponsored over 150 Master in Public Policy degrees for Japanese ministry officials at the Ford School since 1973.

“Because I worked for the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport, what I wanted to study at IPPS was economic policy and other things related to domestic policy,” Shibuya said. He laughs now at the thought that he was not so interested in international relations or international trade at the time.

Shibuya found classes like microeconomics and organizational design very practical and directly useful in his subsequent career. But it is Professor Paul Courant’s cost-benefit analysis class that he credits for helping him become an expert in the analysis of infrastructure policy and transportation policy. “At that time, more than 30 years ago, benefit-cost analysis was very new to the Japanese government,” Shibuya said.

He didn’t know it then, but the same policy evaluation skills would come in handy when he was recruited to take a leading role in international trade negotiations.

Before Japan joined negotiations to establish the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2013, the Japanese government was reluctant to enter free trade agreements in part because the politically powerful agricultural sector was very opposed to opening the market for agricultural goods.

In order to participate in the negotiations for the 12-nation free-trade agreement spearheaded by the Obama administration, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe decided to centralize TPP negotiations and decision-making into one office directly under the prime minister’s control. Before, negotiations had been divided ministry by ministry with each office negotiating on equal footing for the sectors within its purview. This made it difficult to offer a unified voice and to resolve the differing interests of the Ministry of Industry, which sought greater trade openness and those of the Ministry of Agriculture, which opposed it, according to Shibuya.

Shibuya was recruited to this new TPP headquarters in part due to his policy analysis expertise but also because he could play a neutral role between agricultural and industrial interests, given that he was coming from the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport.

The negotiation has been both with international partners and with domestic constituents, where Shibuya’s experience in domestic policy has been key. The new TPP headquarters was charged with creating a policy package that would mediate the impact TPP would have on farmers as well as small and medium industries. “In that scene, the knowledge I got from IPPS or the Ford School was very, very, very useful,” Shibuya said.

Before the negotiation even started and during the more than three years of negotiations, Shibuya went before the ruling Liberal Democratic Party many times to persuade them about the benefits of participating in TPP, give assurances that they would not go over negotiating red lines set by the parliamentary group, and offer measures to strengthen the Japanese agricultural industry. The TPP agreement was approved by the National Diet, Japan’s legislature, after 133 hours of deliberation.

“After concluding the TPP negotiations I thought I was released from my office and would go back to my home ministry,” Shibuya said.

But when President Trump decided to withdraw from the TPP, Japan took the lead with the remaining countries to finalize an agreement and Shibuya’s return to his home ministry was postponed. “We had to start a new project of TPP 11, which is TPP without the United States,” Shibuya said. TPP 11 became effective at the end of 2018.

Now Shibuya’s return to his home ministry has been delayed once again. President Trump and Prime Minister Abe agreed to enter into negotiations for a bilateral agreement in September 2018. What had been the TPP headquarters was charged with leading the Japan-U.S. negotiations.

As the new round of negotiations began, Shibuya’s IPPS background was helpful once more—but in a surprising way. The mood was tense in discussions regarding the industrial sector, Shibuya recalled. Then, he discovered that his counterpart, Jim Sanford, Assistant U.S. Trade Representative for Small Business, Market Access, and Industrial Competitiveness was also a graduate of IPPS–MPP ’92.

“When we found that Jim and myself are alumni of the University of Michigan, we became good friends and the negotiation started going very smoothly,” he chuckled.

“That is partly what we have in mind by having international students and having some breadth of background in the class,” said Paul Courant after learning about IPPS alumni meeting on opposite sides of the table. “It is a very important Michigan value and this is a very nice outcome of it,” Courant said.

The exchange with Japan that brought Shibuya to IPPS continues at the Ford School today. “Our longstanding partnership with the Government of Japan remains critically important to us,” says director of student services Susan Guindi. “We benefit from the expertise and contributions of the ministry students who come each year. They broaden and strengthen classroom dialogue and grow our students’ co-curricular understanding of and admiration for Japanese culture and values.”

Editor’s note: on August 25 Japan and the U.S. reached a preliminary trade agreement; many details are yet to be resolved, and the work continues.

Below is a printed version of this edition of State & Hill, the magazine of the Ford School. View previous editions.