As the Biden administration embarks on its first hundred days, experts from the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy have produced a series of policy briefs on key issues. Download the PDF of this brief or read the web-formatted version below.

By Celeste Watkins-Hayes

Jean E. Fairfax Collegiate Professor of Public Policy; University Diversity and Social Transformation Professor

Overview

The U.S. needs a targeted approach to ensure the COVID-19 vaccine will be accessible, deemed trustworthy, and utilized by Black and Brown communities, low-income populations, and other socially disadvantaged groups that the healthcare system has systematically and historically underserved and mistreated. The challenge is clear: without a robust strategy to reach those populations, we could witness an even starker COVID-19 divide, with one segment of the population still grappling with COVID-19 years after the advent of life-saving drugs. Given the overlap between the populations most affected by HIV and COVID-19, the HIV safety net has a critical role to play in ending the COVID-19 pandemic. By shoring up and expanding the HIV safety net, we have the opportunity to fight two of the most impactful infectious diseases of the present day by targeting the health disparities that drive both.

Why the issue is important

The HIV safety net consists of policies like the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency (CARE) Act, healthcare and social service providers, advocates and activists, researchers, and policymakers contributing to the U.S. HIV/AIDS response.

There are four key strategies behind the HIV safety net:

- Provide access to healthcare, including mental health services and medications.

- Recognize the relationship between healthcare and economic assistance, understanding that meeting basic needs like housing are forms of healthcare.

- Provide extensive social support such as peer-led services, case management, and support groups to help individuals address the underlying challenges and traumas that undermine health outcomes.

- Create a path to civic engagement for populations of focus. The HIV community recognizes that engaging populations in leadership training and job opportunities not only generates the next HIV workforce but also helps people build skills and seize opportunities for social and economic mobility.

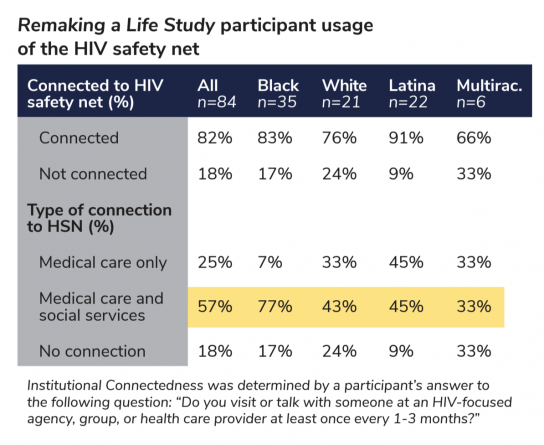

This wraparound service model has proven to be one of the most effective ways to respond to health crises. In my study of 84 women of diverse backgrounds living with HIV, the HIV safety net helped many achieve health, social, and economic stability and inspired some to become change agents in their communities. Study participants exhibited a high level of connectedness to the AIDS safety net, with 82 percent affirming that they visited or talked with someone at an HIV-focused organization, agency, group, or healthcare provider at least once every one to three months. The majority (57 percent) described themselves as visiting both a healthcare provider and an agency that provided social support such as case management. Racial differences were also noteworthy, with poor Black women utilizing social services along with healthcare services in greater numbers than their white or Latina counterparts.

This suggests that the HIV safety net offers both a potential model and existing infrastructure to reach populations disproportionately impacted by COVID-19.

Policy solutions

The HIV safety net incorporates several cultural elements that could prove useful in responding to COVID-19:

- Create strong linkages between communities and government to shape resource allocation and the coordinated epidemic response. Community members can serve as trusted messengers, engaged outreach workers, and valuable problem solvers.

- Value the importance of storytelling. As we saw with HIV, having people with COVID-19 tell their stories is critical for sharing public health information, educating the public, and building policy consensus.

- Utilize trauma-informed care. Attention to various experiences of trauma experienced by underserved populations should inform the healthcare approach.

- Train HIV counselors who currently offer testing services and treatment referrals to be COVID-19 counselors. These individuals are already trained to have confidential, supportive, and trauma-informed care conversations with individuals about their risk profiles, prevention strategies, and treatment options.

A focus solely on biomedical innovations (“getting pills into bodies” to address HIV and “getting vaccines in the veins” in the case of COVID-19) is likely to fail. We can engage the existing HIV safety net and expand it to pivot toward the fight against COVID-19, bringing its tools, networks, and experiential knowledge to bear in some of our most vulnerable communities.

More information

Watkins-Hayes, Celeste. Remaking a Life: How Women Living with HIV/AIDS Confront Inequality. University of California Press.