African countries are experiencing a surge in COVID-19 cases, and the African Center for Disease Control (CDC) is calling on nations to adhere to the basic guidelines of disease containment -- wearing masks and social distancing. The director of the CDC, Dr. John Nkengasong, said those measures “are the only vaccine we have,” as distribution of actual doses continues to lag.

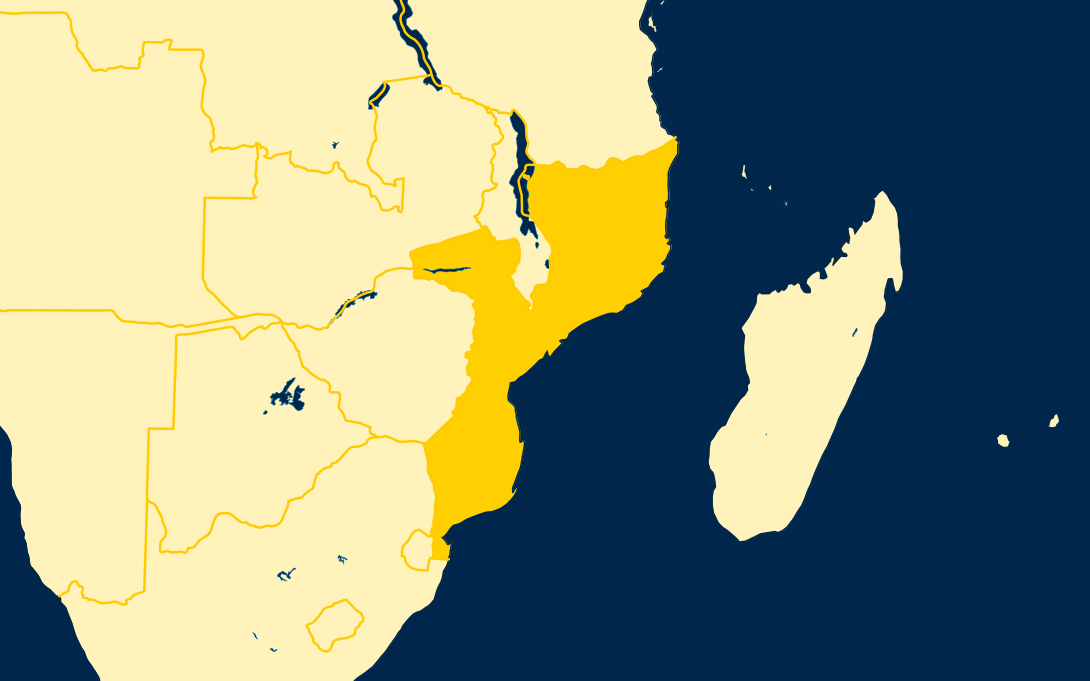

Research by Ford School professor Dean Yang, Ford School PhD student James Allen IV and colleagues has examined the best methods of promoting adherence to social distancing, in this instance in Mozambique, where he has been conducting a number of studies over more than a decade.

In a working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, “Correcting Perceived Social Distancing Norms to Combat COVID-19”, Yang et al assert that informing people of high rates of community support for social distancing can encourage them to do more of it when COVID-19 cases are high.

When first asked, the Mozambican study population underestimated the rate of community support for social distancing, believing support to be only 69%, while the true share was 98%.

Informing people of the high rates of community support can have an ambiguous effect on social distancing, depending on which effect dominates: a “perceived-infectiousness effect” -- that the disease is more infectious than previously thought -- or a “free-riding effect” -- when individuals realize that others’ good behavior gives them less private gain from social distancing themselves.

The “social norm correction” treatment, informing people of true high rates of community support for social distancing, was randomly assigned. The research team then measured respondents’ social distancing behavior, using self-reporting as well as asking others in the community about the respondent.

The methodology was novel in two ways. “Most prior studies ask respondents to self-report their social distancing behavior. When we do so, 95% claim to be social distancing, though we suspected that this is an optimistic overestimate,” says Allen “So our first improvement is to also ask respondents to self-report several specific social distancing actions, and our second improvement was to ask study respondents to report on their social interactions with each other. By these measures, the actual share observing social distancing was just 8%.”

The study shows that the impact of the treatment differed across localities with different disease prevalence: “where COVID-19 caseloads are high (where the perceived-infectiousness effect dominates) treatment increases social distancing, but it decreases where caseloads are low (where free-riding dominates).”

The research also looked at randomized local-leader endorsements of social distancing and found the interventions to be ineffective.

Yang concludes, “As COVID-19 case loads continue to rise, interventions like our ‘social norm correction’ treatment should help promote social distancing.” He continues, “And beyond COVID-19, our findings suggest that similar public health messaging about social norms of support for preventive measures may help in the fight against other infectious diseases.”

The research, in the Beira region of central Mozambique, was conducted over the phone between July and November 2020. The paper’s other authors include Arlete Mahumane, James Riddell IV, Tanya Rosenblat, and Hang Yu.

You can read the complete paper here and visit the project website here.