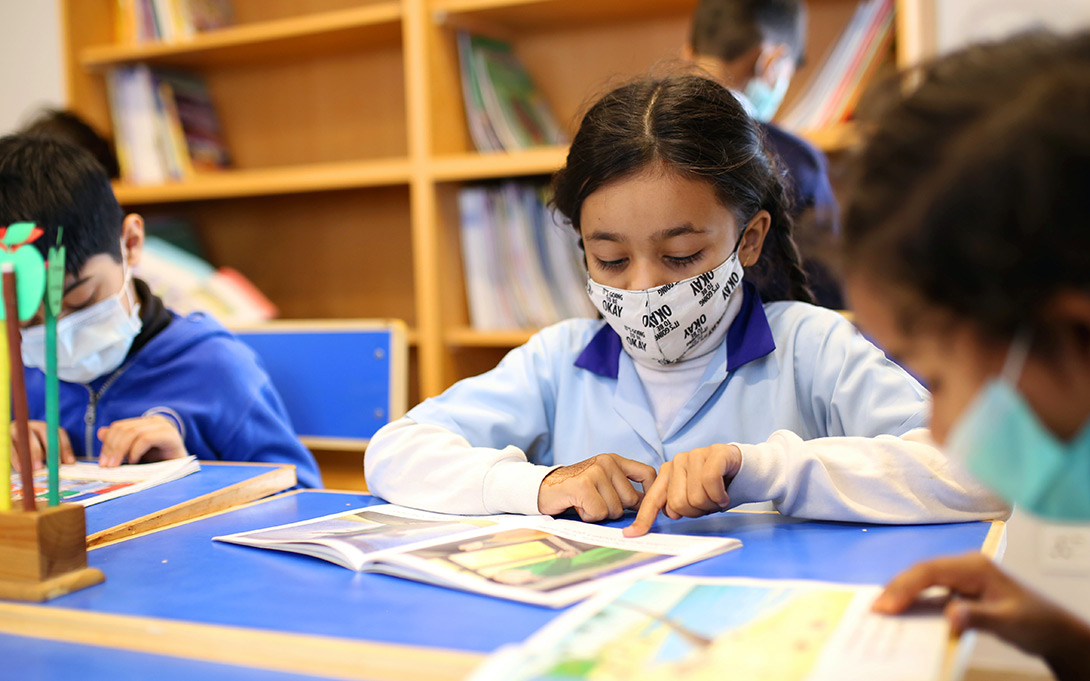

TAYLOR—While groups of first graders work in clusters at pods around the classroom, four children face their teacher at a U-shaped desk, backs straight and eyes alert as she deals cards to each of them.

They're playing "Chocolate Chip Count," a game that will teach them basic math skills almost without them knowing it. It's the educational equivalent of hiding vegetables in the macaroni and cheese. And the kids at Randall Elementary School in Taylor love it.

The cards feature chocolate chips that the kids count and then write their sums on a blank card. One young girl reads out her cards "10 plus five equals 15."

"How did you know that?" the teacher asks. After they answer, the teacher tells them to feed the card to the monster face attached to a plastic jar.

"I really love math. Playing the game really helps me find out more math problems and, it's really fun," said Kendall Goins, 7.

Another game the kids call stinky socks involves children hanging numbers on a clothesline in order from 1 to 20. If they pull a stinky sock card, all the cards come down and the game begins again.

"I'm really good at stinky socks," said Colten McClure, 7. "When I play math games, I feel nice."

Liz Biddle, a school improvement coordinator for the Taylor School District in Wayne County, was the first to suggest trying High 5s, a math enrichment program developed by the University of Michigan to help close the achievement gap. The hands-on, small-group program is being implemented for kindergartners and first graders at Randall and Myers schools in Taylor.

Biddle said that results from the 2017-18 school year indicated that 50% of Randall's kindergarten students were scoring at grade level by the end of the year. One year later, 70% of the students were performing at grade level.

"So we had almost all kids on grade level before they left us, which was amazing," she said.

The first five years of a child's life are considered the most critical for development, but learning opportunities lag for many children, particularly those from low-income households, said Robin Jacob, associate professor and founder of U-M's Youth Policy Lab.

A study found the program increased kindergartners' math performance by 15%. As the name suggests, students are given plenty of positive reinforcement as they progress.

Programs such as High 5s are important to balance out the emphasis placed on literacy skills in the early grades, Jacob said.

"We wanted to make math learning fun. There's a lot that is fun about math, and it is often taught in a way that makes kids feel anxious and not inspired," she said. "And so we wanted to have their early first experiences with math be something that was really joyful and exciting so that they would have positive feelings toward math as they continue their education."

Early math instruction is highly predictive of childhood success on a number of different outcomes. Early math predicts both later math and reading skills. It predicts the likelihood of graduating from high school and of attending college, Jacob said.

"We have seen with the early math work that we've done in New York City that participation in preschool and kindergarten math enrichment leads to improved outcomes in third grade," she said. "We've seen a lot of success in Taylor, and we are hoping to engage with other school districts across the state so that we can share the program with more teachers and young students throughout Michigan."

Jacob and fellow U-M researchers Anna Erickson and Kristy Hanby developed the High 5s program and associated training with MDRC co-collaborators Shira Mattera and Pamela Morris. It was first tested in 24 New York City schools and produced positive results for student math skills. The program was originally inspired by the Building Blocks preschool curriculum developed by Doug Clements and Julie Sarama.

Cynthia Meszaros, principal of Randall Elementary School, said she's been pleased by the program and how it's supported students in the kindergarten and first-grade classrooms.

"High 5s brought in all the pieces that helped children build on their success," she said. "When kindergartners aren't successful, then you have academic and behavioral struggles."

First-grade teacher Lindsey Barnard said at first she was apprehensive about implementing a new curriculum in the classroom with everything else going on.

"But fitting High 5s into our math curriculum seemed pretty seamless," she said. "We already do small groups every day. Usually, those small groups are intervention groups, and so the High 5s curriculum took out that extra planning that we needed to do for those intervention groups."

She received training from the U-M team and a chance to provide feedback on how it was working.

"I can use this game to help reinforce addition or help reinforce shapes. So it's definitely giving me a different tool in my toolbox," Barnard said. "I was surprised at how well the program still allows you to be flexible in your teaching. I can use the games and still use my own teaching style to present it."

Part of the program also includes monitoring by U-M to find ways to fine-tune the program. Deb Hubbard, a research associate with the Youth Policy Lab, visits Taylor periodically to observe how students and teachers work with the High 5s curriculum.

The games are designed to "bring math out of the play," she said. And because the teacher is interacting with the students while they play, they can talk to the students about their mathematical thinking and learn the strategies they use to come up with answers. And that gives teachers information about what each child understands and also lets the child know that their ideas are valued.

"And then they can really see their kids as individual learners and know what is the next best instructional move for that child," Hubbard said. "What students learn is fundamentally connected with how they learn it. High 5s promotes new practices to build these teachers' skills and confidence as exceptional math educators, which is vital to improving student achievement."

While early literacy interventions are widespread, similar programs in math are just beginning. And that's good news for some students.

"I like math more than reading when I play math games with my teacher," said Estelee Chivelli, a first grader at Randall Elementary.

This story was written by Greta Guest and originally published by Michigan News as part of its "This is Michigan" series.