Many states invest heavily in their institutions of higher education only to see graduates leave for employment opportunities. To better understand that dynamic, Ford School Professor Kevin Stange and his colleagues developed a new measure of labor markets using data from LinkedIn about alumni and their movements. In their paper, “Grads on the Go: Measuring College-Specific Labor Markets for Graduates,” Stange and his colleagues introduce and apply their new measure, which uses data about the locations of alumni and their alma mater to describe their relationship.

“We show that the social benefits of public investment in postsecondary education disproportionately accrue to high-wage and urban/suburban areas due to graduate mobility, which we can now quantify at sub-state and institution-specific levels,” they say. “We also find that regional public universities tend to produce the greatest number of 4-year college graduates who remain and work in-state per dollar of state funding.”

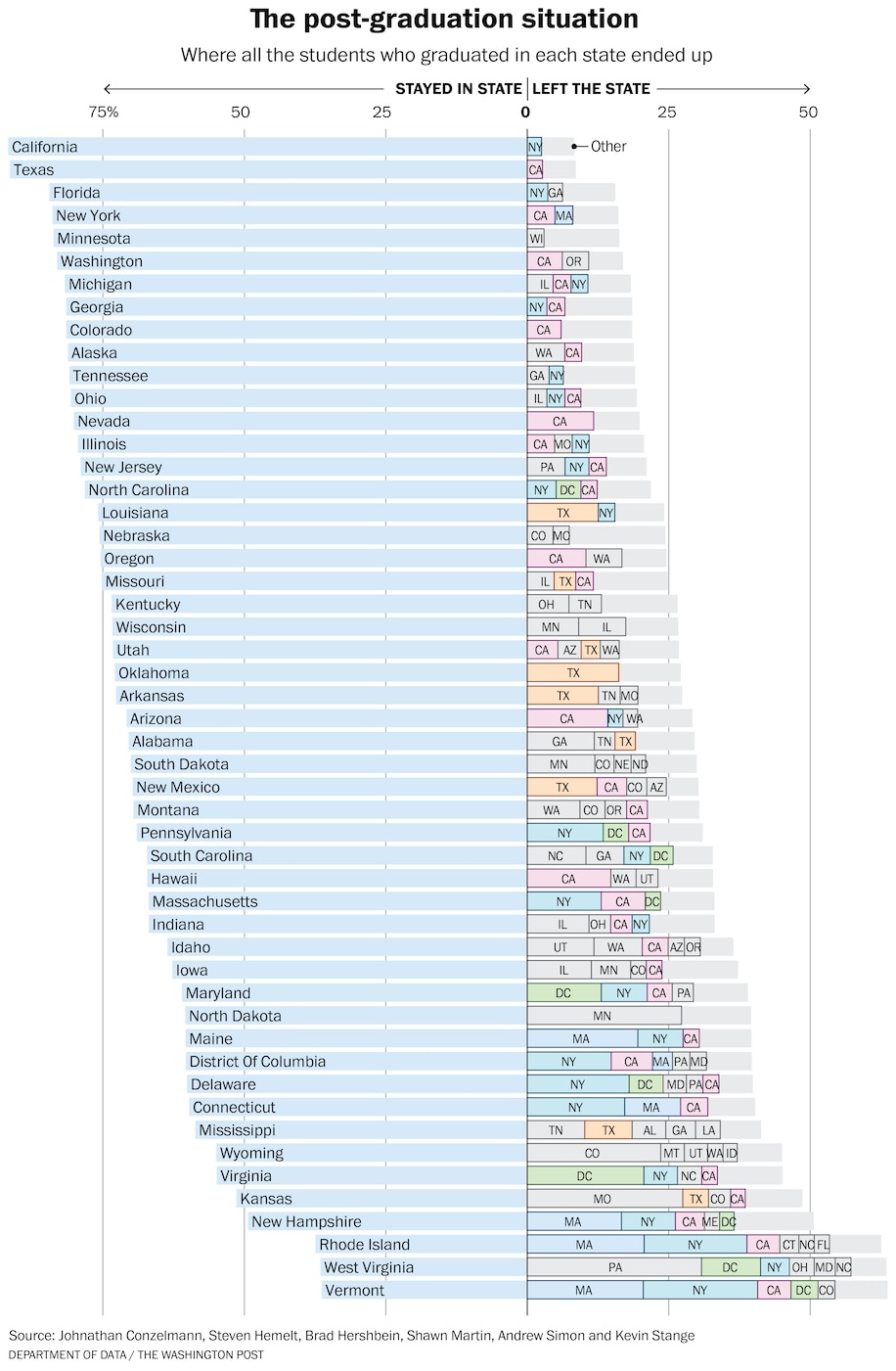

Stange and his colleagues use this finding to flesh out the idea of “brain drain,” or the loss of homegrown, college-educated talent to other areas. They conclude that the social return on investment for a state depends on the distribution of alumni across the country. Because of this migration, states may not receive the full value of their investment in higher education.

“High mobility rates decrease the value of public investment by states, potentially leading to an under-provision of the services as other states ‘free-ride,’” the researchers find. “State flagships, despite having much higher graduation rates, have greater out-of-state migration and higher spending, lowering the number of graduates retained in-state per state dollar spent.”

These results, the researchers argue, are just a first step toward understanding the relationship between geographic and economic mobility of low-income students in higher education — creating implications for how best to serve those students.

“While some institutions may do well by their low-income students by fostering close ties to their local labor markets, it appears students also gain from institutional networks outside the most proximate labor market,” Stange and his colleagues write.

The experts also draw upon their novel measure to explore the role of migration in understanding the social return to public investment in higher education.

These applications are just two examples of how the new measure of labor markets near institutions can be used. The researchers suggest that there are many more possibilities to apply this measure to learn about recent graduates and the labor market.

“Postsecondary institutions play an important role in labor markets, constitute a target of substantial public investment, and are crucial cultural and political institutions,” Stange and his colleagues conclude. “Simply knowing where an institution's graduates end up living after graduation is a hurdle many analysts struggle to surmount. Our novel measure helps to fill this analytic gap.”

Among Stange's co-authors are Shawn Martin and Andrew Simon, U-M and Education Policy Initative (EPI) graduates, and Steven Hemelt and Brad Hershbein, EPI affiliates.

This paper was originally published in the National Bureau of Economic Research. Read the entirety of “Grads on the Go: Measuring College-Specific Labor Markets for Graduates.”

Information from the study was featured in the Washington Post and Detroit News:

States with the worst brain drain, Washington Post, September 9, 2022

Michigan's brain drain: Which colleges lose the most graduates and why they leave, Detroit News, September 18, 2022