The UMich Votes coalition is aiming to increase voter registration and turnout among students on campus

University of Michigan students are continually breaking voter registration and turnout records. Some 78 percent of U-M students on the Ann Arbor campus voted in the 2020 election, up from 60 percent in the 2016 election, and 44 percent in 2012. And though only 52 percent of eligible voters turned out for the 2022 midterm election, it overshadowed the 30 percent average at peer institutions, according to the National Study of Learning, Voting, and Engagement.

However, there’s still a disparity between student registration and students who turn up to the polls. In 2020, 88 percent of registered student voters cast their ballots, meaning more than 4,000 U-M students who were registered to vote skipped the election.

“There’s always a gap between those who register and those who turn out,” says Elizabeth Netcher, the Ginsberg Center’s democratic engagement manager. “We have almost a 90 percent registration rate, which is amazing. But there’s this gap in turnout and we’re still trying to figure out why that is. . . . We’d really like to see those registration rates and turnout rates be almost the same.”

The Ginsberg Center is a community and civic engagement center at U-M that supports partnerships such as the Big Ten Voting Challenge, a competition amongst Big Ten schools to have the greatest student voter turnout. It’s also one of several campus partner organizations — along with TurnUpTurnout, the Campus Creative Voting Project, and others — that comprise UMich Votes, a nonpartisan campus coalition aiming to increase student voting on campus.

As the nation prepares for a hotly contested presidential election, leaders at the University of Michigan are leveraging research, accessibility, and education to increase voter registration and turnout among students on all three campuses.

The Young Vote

Most current U-M students are part of Gen Z (those born between 1997-2012) and may be the most politically engaged generation yet.

According to the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement at Tufts University, in 2022 Gen Z voted at a higher rate in their first eligible midterm election than previous generations, with 28.4 percent of people ages 18-24 casting a ballot. When other generations made up that age group, millennials voted at a significantly lower rate of 23 percent in their first midterm in 2006 and 23.5 percent of Gen Xers in their first midterm in 1990.

In the state of Michigan, high student voter registration and turnout in 2022 may be because of the local issues on the ballot affecting them. No matter the reason, voter turnout among young people can change the course of an election. Forty-one million members of Gen Z will be eligible to vote in the 2024 presidential election, including 8 million new young people who will be eligible to vote for the first time.

“Students may say, ‘My one vote can’t matter.’ It really can, actually. You can truly make a difference,” Netcher says.

While enrolled in college, students can register to vote with their residential or local address. One of UMich Vote’s efforts is to inform students of their options early enough that they can decide where to vote, register, and get an absentee ballot in time, if needed.

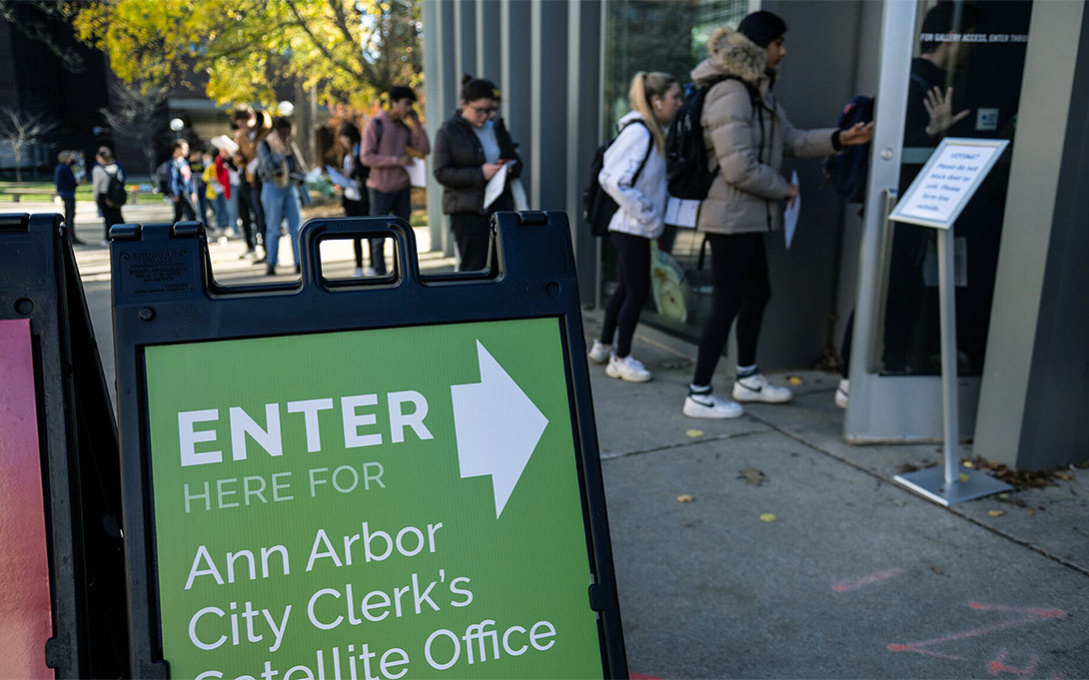

In 2022, some students waited more than six hours to vote, with lines wrapping around the U-M Museum of Art, a voting location on campus, late into the night. However, this wasn’t so much caused by long voting lines but rather by those needing to submit a same-day registration to vote.

That year, the state of Michigan passed a new law that offers nine days for voters to get to the polls and have the same voting experience as they would on Election Day. UMich Votes hopes this will reduce wait times and offer more opportunities for students, staff, and faculty to get to the polls.

It’s a balance to give students all the information they need without overwhelming them, but Dave Waterhouse, ’88, the associate director of the Ginsberg Center, wants students to know voting “isn’t scary.”

“It’s actually a pretty simple process. It’s really important. There are a tremendous amount of local and regional things on the ballot again this year that have a real impact on student’s lives and the time they spend here, and it’s really important to have a voice in that,” he says.

Year-Round Democracy

Getting students to the polls doesn’t begin in November. TurnUpTurnout (TUT) hosts events throughout the year to educate students on current issues and help them register to vote.

The student-led organization offers classroom presentations and walks to the polls, but their most successful events are Dinners for Democracy, which are educational presentations about current political issues, created by and for students.

“Students are really interested in hearing a non-biased perspective on ‘hot button’ topics. I think students are tired of always being fed very extreme perspectives. So it helps to have a presentation and group discussion,” says Maurielle Courtois, a political science major and co-president of TUT.

All of UMich Votes is nonpartisan, but Courtois says many students assume they’re liberal or Democrat-associated.

“It’s hard to combat the perception that we’re inherently partisan because we’re on a college campus, but the way to diffuse that situation is just by going back to the fact that all of our initiatives are nonpartisan, and we don’t do any endorsements of any kind — local, state, or national. It truly is just about voter registration and voter turnout,” she says.

Penny Kane, ’22, who organizes TUT events on the Dearborn campus, faces similar challenges.

“We try to let [students] know you’re not making any commitments. You’re just making sure that when you want to vote, you’re ready to vote,” Kane says.

Waterhouse says it’s key to have students like those from TUT as part of UMich Votes.

“We, as staff and faculty, can put the word out there, we can build the infrastructure, but for many students, it’s what their peers are doing and thinking about that makes a difference.”

Welcome In

As students arrived back on campus this fall, guests to U-M’s Museum of Art (UMMA) were greeted by a striking array of voting pins, a U.S. map where they could place a pin where they planned to vote, an eight-foot-tall sample ballot, and more.

This was the first installment of the Campus Creative Voting Project, which uses art and design to make voting more approachable, particularly for U-M students. The second installment opened on Sept. 24, transforming part of the museum into a lively civic space where students and local residents can register to vote, request an absentee ballot, discover nonpartisan resources, and vote once the polls open, thanks to a close partnership with the Ann Arbor city clerk. A second campus voting hub at the Duderstadt Center Gallery on North Campus will open on Oct. 21.

The idea for the Creative Campus Voting Project began as a class, co-taught by Stephanie Rowden and Hannah Smotrich in 2018, where students designed a voter engagement campaign for their peers. Now, informed by insights from behavioral science and careful attention to election law, it strategically designs materials, spaces, and experiences for students to learn about and meaningfully engage with voting. This includes everything from the colors and fonts used in environmental graphics, to clear and precise instructional language, to the ways peer mentors are trained to welcome students and answer questions, all aimed at making voting clear, trustworthy, and welcoming.

“We’re always interested in finding ways to engage, educate, and help new voters participate. We’re particularly focused on how design can address the psychological and knowledge barriers, knowing that, for most students, voting is a new, overwhelming, and confusing process,” Smotrich says.

More than 8,000 ballots were collected at UMMA in the 2020 election and Rowden says it’s “tremendously gratifying” to see students use the campus voting hub.

“They feel extremely accomplished and they feel like they’ve engaged in a really important adult rite of passage, but they’ve also been able to do it in the context that makes sense for them,” Rowden says.

For Rowden and the University, all these efforts are about establishing a lifelong relationship with civic engagement.

“There are a lot of psychological tipping points and we forget if we’ve been voting for a long time that there’s actually many decision points along the way even before you are voting on a ballot. So what can art and design do to help clarify the process and welcome people into the experience?” Rowden says. “Knowing that, if you have a good first experience, it has the potential for laying the foundation for a lifelong relationship to voting.”

Year of Democracy

Voting is a powerful tool for shaping the future. As the U.S. approaches another presidential election, U-M stands at the forefront of a larger movement to harness the influence of young voters.

“We’re taking very seriously this opportunity we have to help students understand how they can become involved and really confident as citizens,” says Jenna Bednar, ’90, the faculty director of UMich Votes and democratic engagement.

As part of Vision 2034, the University’s 10-year strategic plan, U-M’s inaugural theme year is the Year of Democracy and Global and Civic Engagement, often referred to as simply the Year of Democracy. It seeks to answer the guiding question, “How do we inspire engagement in our democratic future?”

This year begins with a focus on civic engagement in the fall semester with UMich Votes, but will extend beyond that in 2025 to explore the history of activism on campus, democracy research, and how U-M can continue to be a leader in this space.

One aspect of the Year of Democracy will explore how to “engage across difference,” Bednar says, to appreciate multiple perspectives and find common ground when possible.

“There can be multiple ways of seeing an issue, and that might help to develop some sympathies for others. We’re in this era of polarization where we’ve been encouraged to think about people who see the world differently from us as being somehow less than human. That gives us permission to not just be disrespectful, but even violent toward others,” Bednar says, adding that one goal is to “reconnect the bonds within our community.”

Despite the political unrest of a presidential election year and activism on campus, Bednar says it’s even more important to address the issues U-M and the community are facing.

“You could pretend that problems don’t exist — on our campus, in our state, in the country, in the world. Or you could say, ‘Can we do something?’” Bednar says. “We’ve decided we’re going to try.”

By Katherine Fiorillo, Michigan Alum