How much control should we have over our likeness? Our anonymity?

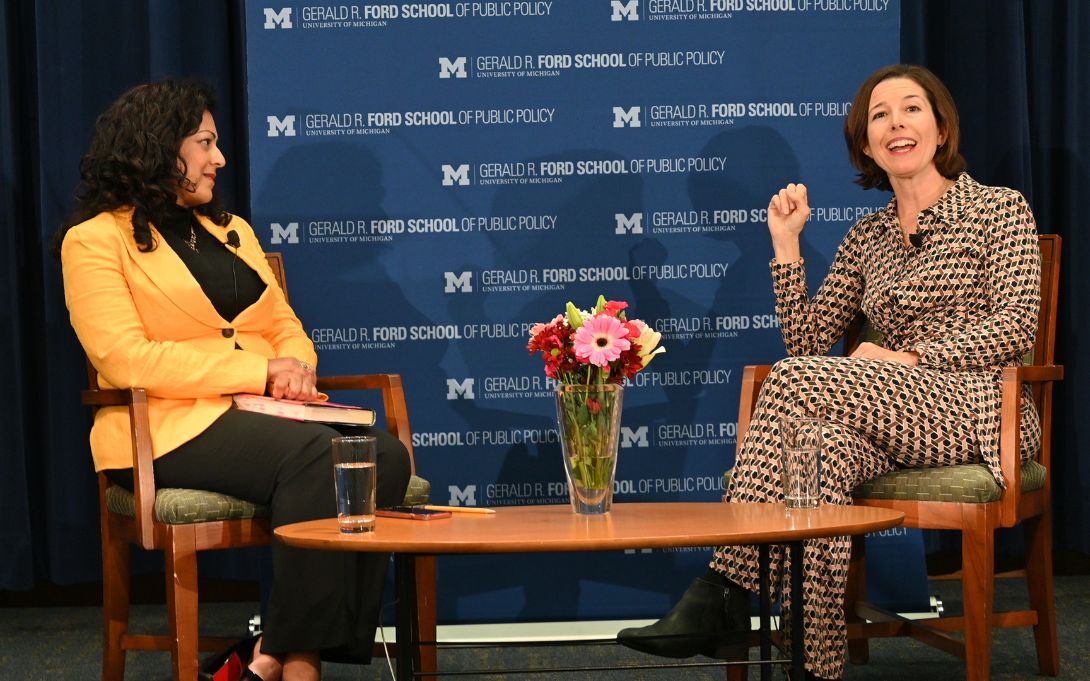

Nearly 200 attendees confronted these questions at a Ford School event with New York Times technology reporter Kashmir Hill, in conversation with Science, Technology, and Public Policy (STPP) director Shobita Parthasarathy.

Hill’s new book, Your Face Belongs to Us: A Secretive Startup's Quest to End Privacy as We Know It, documents the rise of a small AI company that gave facial recognition to law enforcement, billionaires, and businesses, threatening to end privacy as we know it.

“This is kind of the world that we live in [in the United States] where there really is no protection of your private information,” Hill explained. In Europe, she says, information use is more regulated. For example, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) fines companies that misuse biometric data, and ensures citizens retain control over their personal information. In contrast, the United States lacks a unified privacy regulator, leaving enforcement scattered and inconsistent.

“I talked to Senator Edward Markey because he’s a big privacy hawk,” Hill said. “And I asked him, how has Congress not managed to pass a privacy bill yet? He said it's the tech industry that lobbies against it. That's the number one reason.”

Civil rights organizations have stepped in where government action lags. The ACLU, for example, played a critical role in supporting Robert Williams, a Michigan man falsely arrested due to a faulty facial recognition match.

“I feel like every story I do keeps coming back to this,” Hill said. “We just don't have a lot of protection for where our data goes… there should really be a nationwide privacy law, or every state should have privacy laws that protect people.”