Before Nixon's fall, before Agnew's fall, Gerald R. Ford spent 25 years in the U.S. House of Representatives. But while everyone remembers his presidency, and the "extraordinary circumstances" under which he assumed the post, too few recall the influential role he played as a moderate Republican in Congress.

In 1946, after the close of World War II, Gerald Ford returned from service in the U.S. Navy to his hometown of Grand Rapids, Michigan and resumed civilian life. Almost immediately, the young Ford became immersed in a wide variety of political and civic causes. He was working as a lawyer, with the hopes of making partner some day, and the idea of running for an elected office was a distant and somewhat hazy dream. So Ford followed local political happenings with his innate curiosity, but wasn't deeply involved until he found himself disagreeing with his district's Representative, Bartel Jonkman, on a matter that concerned him deeply.

Jonkman—like many Republicans of the era—was a staunch isolationist when it came to foreign policy. He strongly opposed President Truman's plan to assist in the post-war reconstruction of Europe, including the reconstruction of former enemy states, Germany and Italy. Ford was a Republican too, of course, but one who had become convinced during his service in the Navy that America had a responsibility to promote and preserve world peace, and that rebuilding war-torn nations—whether friend or foe—would be a good way to do that. So Ford chose to run against Jonkman. Though Jonkman was a powerful politician, Ford ran a smart campaign, and won with an impressive 60.5 percent of the votes, joining the U.S. House of Representatives in 1949.

At the age of 37, before the end of his first term in Congress, Ford was appointed to the quiet but powerful House Appropriations Committee, where he would serve for more than a decade. During these years, Ford worked to save taxpayer dollars, advance government efficiency, and invest in America's military to preserve the peace. In 1961, the American Political Association presented Ford with its Congressional Distinguished Service Award, calling him a moderate conservative, highly respected by both parties, "who eschews the more colorful publicity seeking roles in favor of a solid record of achievement in the real work of the House: Committee work." James Cannon, author of Gerald R. Ford: An Honorable Life, writes, "To the Association, as in the House, Ford was not a show horse, but a workhorse…." Ford didn't write legislation, or drive new Republican bills, but he was influential.

Throughout the 1950s, Ford served on a number of other subcommittees, including the Foreign Operations Subcommittee and the select committee that drafted legislation leading to the creation of NASA. In the 1960s, he was tapped to serve on the Warren Commission, investigating the assassination of John F. Kennedy and the murder of Lee Harvey Oswald. And he might have gone on in this fashion indefinitely, happily serving Congress far from the limelight, if not for a series of events that crippled his party.

In 1964, Ford watched with concern as the Republican National Convention was dominated by Senator Barry Goldwater and other deeply conservative members of the party. The senator's strident speeches and systematic exclusion of moderate Republicans left Ford dismayed, and on election night, his fears were realized. Goldwater's extremism alienated many voters, and the 1964 election cost the party three dozen seats in the House.

This is when Ford gave in to the urging of his moderate Republican peers and agreed to run for House minority leader. In 1965, he won the office by four votes, becoming the highest-ranking Republican in Congress. As minority leader, Ford attempted to develop more substantive and positive Republican platforms. He campaigned for moderate Republican candidates, and helped to narrow the gap between the Democratic majority and Republican minority in the House. And along the way, he also did what the House minority leader is supposed to do: he engaged with the majority, across the aisle, to address issues of joint concern.

|

|

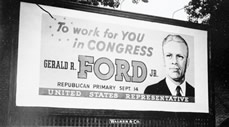

A 1948 billboard in Grand Rapids, Mich. during Gerald Ford's first campaign for the House of Representatives. |

Democratic Representative John Dingell, the longest-serving member of Congress, remembers Ford fondly. "When it comes down to it, the best political leaders are those who put partisan labels and rhetoric aside to best get the job done." Though from opposing parties, Dingell and Ford did just that, he says.

In 1973, when Richard Nixon nominated Ford two days after Agnew's resignation—setting in motion the "extraordinary circumstances" under which Ford would later assume the presidency—Congress deliberated, as it must, but only briefly. Ford's bipartisan leadership, civility, work ethic, and modesty had earned him the respect of his peers. His nomination was confirmed by an overwhelming majority of Republicans and Democrats in both houses.

Photos: Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library

Below is a formatted version of this article from State & Hill, the magazine of the Ford School. View the entire Fall 2013 State & Hill here.