Philip Power, class of 1960, served on the University of Michigan Board of Regents from 1987 to 1999. Power, his parents, and his wife Kathy have supported the U-M Museum of Art, U-M Student Publications, the University Musical Society and the Center for the Education of Women. Lead gifts from the Powers had built the Power Center for the Performing Arts in 1971. But when, as a regent, Phil Power went out to advocate for the Ford School, he encountered some pushback.

“I went to Lansing,” Power recalls, “and I suggested they might benefit from the public policy work being done at Ford. They said, ‘What? The University has no interest in the State! They’re national and international. They don’t care about Michigan.’ I came back, sat with the dean at Ford and said, ‘I just came from Lansing. They think the University is not interested in the region. Let’s work on this.” The result, a few years on, would be the Ford Schools Program in Practical Policy Engagement, nicknamed “P3E,” funded by a $1.5 million gift from the Power Foundation.

Soon after that conversation in Lansing, Power met Elisabeth Gerber, professor of political science and public policy. “Liz was smart, engaging, creative, the best kind of person to collaborate with,” Power says. “I asked her, ‘What would happen if we made education experiential for Ford students, made it humane and practical, the academy going out and meeting the culture?’ I felt we had a responsibility, as a public university, to our state and to students who were residents of that state.”

“Phil’s ambition to transform the way we educate students was completely infectious,” Gerber says. “I couldn’t not say yes. The moment he started talking about it I knew I had a partner in crime.”

Gerber notes the Ford School’s longstanding commitment to the importance of applied learning. After all, the Ford School requires a substantive policy internship for all MPP students. And since the late ‘90s, students have been regularly offered an elective Applied Policy Seminar (APS)—a course that puts students to work on a semester-long commissioned assignment for a public sector or non-profit client.

Gerber led an expansion of the APS, now called Strategic Public Policy Consulting or SPPC, in 2010 and is at the vanguard nationally of professors who practice “engaged learning,” coursework in which students bring classroom skills and knowledge into formal partnerships with external public and private organizations that drive policy.

Power gives an example of real-world engagement from his early work with Gerber. “Liz recruited the head of Ann Arbor Water Services,” he recalls. “Students studied water rates and learned what they meant for citizens and for the infrastructure.” In early 2015, Power and Gerber agreed to go forward with a prototype engaged learning course that included outside mentors. The Power Foundation funded release time for Gerber. Twenty-five students enrolled. Power and Gerber recruited as mentors Paul Hillegonds, former Michigan speaker of the house and senior vice president of DTE Energy, and later, Larry Good, chair, co-founder and senior fellow at Corporation for a Skilled Workforce in Ann Arbor, a leading job training policy and practice organization.

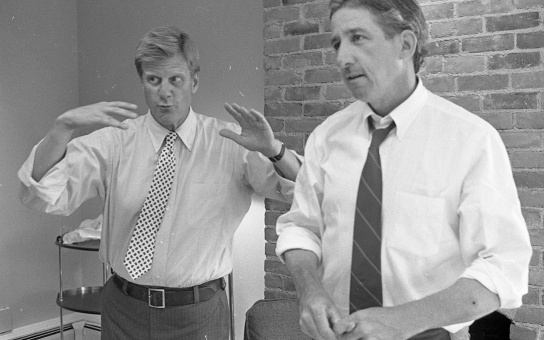

As a student, Phil Power served as editorial director of The Michigan Daily, along-side editor-turned-lawmaker Tom Hayden (right). The two reunited just off campus for a book signing at Power's office in 1988.

Power went next to U-M’s provost, to the dean of the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, and to the associate provost for programs. All agreed that Power’s and Gerber’s concept was what U-M—and the Ford School in particular—should be doing. Gerber taught the course again, with more students.

Soon, Power was asking Michael Barr, Joan and Sanford Weill Dean of the Ford School, “What would you need to make engaged learning a regular part of the Ford School?” Barr said, “Money.” As Power tells it, “I said, ‘Tell me, write to me.’ And he did. The hope now was to meld academic learning with real world experience, thereby making relevant student learning and helping nudge academic culture to make Michigan a better place. That got Kathy and me excited! The foundation decided to fund it, and now we are on our way to building within the university an academic community and a constituency for engaged learning: an idea whose time has come!”

Power says the vision for P3E was built into his DNA. Power spent much of his career running HomeTown Communications Network, Inc. in Livonia, Michigan, a group of 64 community newspapers across the Upper Midwest. “I was interested in what helps a community be better,” he says, sounding very much like the man with a passion for engaged learning.

By 2005, Power saw internet news threatening small-town papers, so he sold HomeTown to the Gannett Company and started a “think-and-do tank” called the Center for Michigan. The center’s mission is to improve life in Michigan by involving ordinary citizens in state and local policy issues. The center publishes Bridge, an online news source (circulation of 1.6 million and three years as Michigan’s best newspaper, per the Michigan Press Association) dedicated to such issues and once again helping communities be better.

“Phil and Kathy are so inspiring,” Liz Gerber says. “They care deeply about Michigan, the university and our future. They have demonstrated this through Bridge, the Center for Michigan, and all their university support. Their gift to the Program in Practical Policy Engagement will help us initiate and cultivate more long-term external partnerships with local government and nonprofits. If the school is thoughtful about and truly engaged in these partnerships, they will ripple out, to the benefit of all. This investment in the future of the state really caps all that the Powers have done.”

“When I was a regent,” Power recalls, “every year I sent 3,000 letters to the people who ran the State of Michigan, telling what the university was doing. In my last letter before leaving office I concluded that, when the history of the twentieth century was written, it would say that public universities were one of the biggest, most significant contributions that the United States had made. Think how valuable a university can be to a state and its citizens if that university gets engaged.Throughout my career I have seen this, and I continue to believe it.”

—Story by David Pratt

Below is a formatted version of this article from State & Hill, the magazine of the Ford School. View the entire Winter 2019 State & Hill.