By Rebecca Cohen (MPP '09)

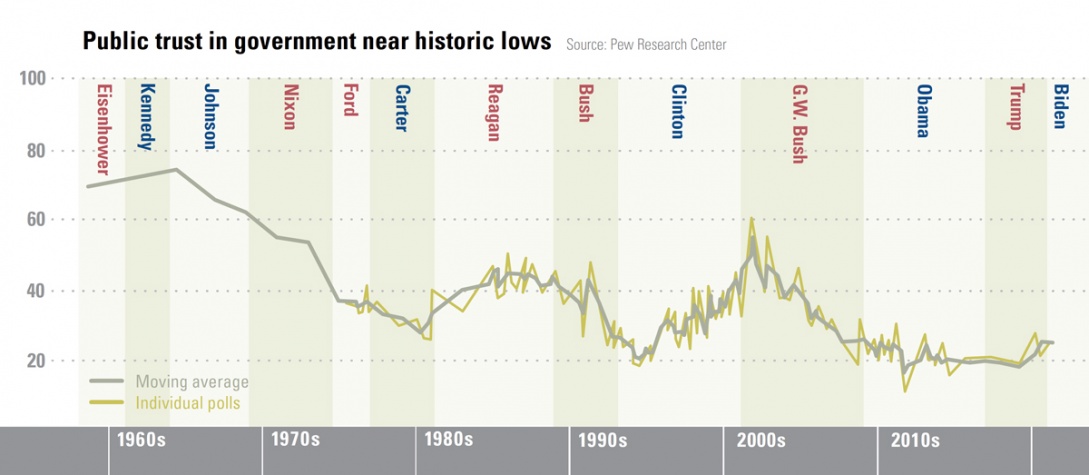

Americans’ trust in government institutions to “do the right thing” has steadily eroded since the late 1960s,1 correlated for many analysts with events such as the Vietnam War, Watergate, the ’70s oil embargo, and President Reagan’s 1981 inaugural address.2

Tom Ivacko (MPA ’93), executive director of the Ford School’s Center for Local, State, and Urban Policy (CLOSUP) says he is “worried that the built up lack of trust has manifested into a more threatening issue: people are losing faith in our system of government itself.

”Preliminary data from CLOSUP’s latest Michigan Public Policy Survey (MPPS) shows a significant increase in those who believe there is “a total breakdown of democracy” at state and federal levels between 2020 and 2021. Local leaders who believe that democracy in the U.S. is in a state of “total breakdown” tripled during this time, and now more than half say it is at or near “total breakdown”. Almost one-third of local leaders describe democracy in Michigan the same way. Importantly, nearly 70 percent of these same leaders rated democracy in their own jurisdiction as “perfectly functioning” or close to it.

This lack of trust, whether in government institutions or the system itself, makes finding and implementing solutions to our communities’ greatest challenges—like policing, COVID-19 responses, and vaccine distribution—even harder.

Drivers of distrust

Government decision-making often relies on the advice from scientists and private industry. That can come at the expense of community expertise, says Shobita Parthasarathy, director of the Ford School’s Science, Technology, and Public Policy program. “Because community knowledge is rarely incorporated into decision making, individuals are less likely to trust these expert institutions,” she says. “And when community knowledge is rejected in favor of scientific knowledge, it masks citizen concerns.” The Flint, Michigan, water crisis is a recent example of state policymakers and regulators ignoring and dismissing resident complaints, she adds. “There is a long history of institutionalized mistreatment of marginalized communities.”

Parthasarathy also points to institutional failures, like the Boeing 737 Max crashes, that can shake public confidence. She says this is especially true when there is poor communication about scientific limitations and uncertainties.

For example, government regulators failed to protect millions of Texans earlier this year when severe storms knocked out the power grid. “Texas has an extremely deregulated electricity grid,” says postdoctoral fellow Josh Basseches, who researches the power of investor-owned utilities in state climate policy. “Decision-making is driven by industry, which led to poor weatherization and poor preparedness.”

“Even though electricity regulation hasn’t changed much since the early 1900s,” Basseches says, “most people don’t pay attention to how the system works until something goes wrong. Utility data isn’t accessible to the average person, so it leads to a lack of engagement and low levels of trust.”

The role of the media

In 2019, half of U.S. adults believed made-up news and information was a very big problem in the country. Pew Research Center found that around two-thirds said made-up news and information had a big impact on public confidence in the government (68%), while more than half said it had a major effect on Americans’ confidence in each other (54%) and political leaders’ ability to get work done (51%). Parthasarathy believes that the spread of misinformation, disinformation, and conspiracy theories are a product of distrust in our government institutions, rather than a driver. “Misinformation is most effective when there is a kernel of truth, and some institutions have behaved badly,” she says.

John Ciorciari, director of the International Policy Center and the Weiser Diplomacy Center, says that the widespread “political tribalism” found in the fragile states he studies elsewhere in the world has intensified in the United States. “The media, at times, deliberately reduces trust in governmental institutions through exaggeration and painting policymakers as morally deficient,” he says. “It’s almost certain there will be a loss of trust when half the population feels like they are not being represented at any given time. This is particularly true for Republicans, but it happens with both parties.”

Lessons from fragile states

Regardless of where you live in the world, “When performance lags—in education, health care, or the economy—it corrodes people’s faith,” Ciorciari says. He explains that for new governments formed in fragile states, trust is earned or lost in feedback loops. “When institutions perform well, people choose to engage and it sustains democratic processes. The government gains legitimacy.”

For example, Ciorciari says that in many fragile states, there is a widespread perception that police are an instrument of power; they are not there to serve and protect, or to uphold the law. New governments often promise to reform the police, and it’s not until the police demonstrate they are different from their predecessors that people begin to comply, cooperate, and enforce norms in the community.

In the U.S., a growing number of people are wrestling with anger and grave misgivings about the fundamental role that police play in communities of color. Ciorciari says that he was concerned that if the Derek Chauvin murder trial had ended differently, many would see this as more evidence of a failed system, and they would withdraw and disengage.

Ciorciari remains hopeful. “Fragile states are fragile because a majority does not believe the government is legitimate. There are pockets of people in the U.S. that have had low trust for a long time. Although that has grown, they are still in the minority. It doesn’t have to take many years to turn it around.” He added that reform advocates can use “high-profile positive performances and seize on that momentum.”

Building stronger trust

“Transparency is the first step to understanding what the problems are, but it’s not the full solution,” Parthasarathy says. ”We need foundational institutional change that takes community knowledge and expertise seriously and includes different perspectives, particularly from communities that are historically marginalized or that are likely to be skeptical.”

Parthasarathy also says increased diversity among government employees and technical experts to reflect communities they serve will help ensure they are asking questions and using methods that take into account different experiences and contexts. “It’s important to consider geography,” for example. “Representing different viewpoints will address a primary concern to both parties.”

Representation also matters in electoral politics, where state politicians have drawn manipulated district maps. In 2018, Michiganders passed a constitutional amendment to fix their gerrymandered congressional districts with a mandate: an Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission will redraw state and federal legislative districts to reflect the state’s diverse population and communities of interest. Ivacko and CLOSUP are currently helping the state understand the mandate and reach out to communities across the state.

The process to redraw the (congressional) districts is night and day from what it used to be. It’s done out in the open for everyone to see and allows people to have their say. Now it is up to citizens to do their part to engage and pay attention.

Tom Ivacko

“The process to redraw the (congressional) districts is night and day from what it used to be,” Ivacko says. “It’s done out in the open for everyone to see and allows people to have their say. Now it is up to citizens to do their part to engage and pay attention.”

While he says the commission should increase public trust, he is concerned about extreme partisanship. “We need to have compromise, and we need to have two parties who believe in the system of democracy.”

To prepare students to be leaders in public service, Parthasarathy teaches analytical methods that engage citizens in decision-making and inspire trust. She also teaches students to consider different perspectives. She says, “If you only focus on fact versus fiction, the only remedy is to convince people of the facts. But if we understand that the interpretation of the facts is shaped by values and knowledge and perspective, it provides a broader suite of interventions that we can use.”

1 Pew Research Center found there was a slight uptick in trust post 9/11 before dropping back to previous levels. The most recent polling show that since 2017 the overall level of trust in the government has remained largely unchanged.

2 In his 1981 inaugural address, President Regan famously said “Government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem.”

Below, find the full, formatted Spring 2021 edition of State & Hill.