State & Hill sat down with the Ford School’s new dean to reflect on her scholarship, her mentors, and Gerald Ford

State & Hill: Tell us about your intellectual journey to leading the Ford School.

Celeste Watkins-Hayes: What you see in my leadership style embodies all of what has been poured into me. I’m blessed with phenomenal mentors and people with whom I have lifelong relationships.

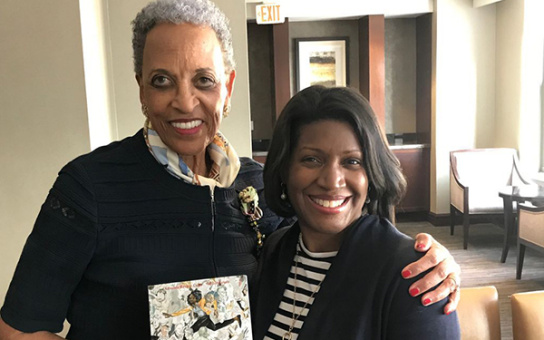

I think of the Civil Rights movement as a long arc and a long movement rather than a moment in time. I view my career as continuing in that long arc and trajectory. When you look at the commonality of my mentors who came up during the 1960s—Dr. Johnnetta Cole, William Julius Wilson, Katherine Newman—they all have an appreciation of and grounding in history. They recognize the importance of being truth-tellers. They understand how to communicate and how to think about the gap between the imagined and the reality. And they also have the ability to bring people along in a shared vision for what might be possible.

Then as a postdoc, I had an opportunity to study here at Michigan with Sheldon and Sandy Danziger. So many of today’s leading social science voices on racial inequality—Mary Pattillo, Waldo Johnson, Rucker Johnson, Sandra Smith, Mignon Moore—have been mentored by them. Sheldon and Sandy believe in deep, humane investments in early career scholars, and they figure out how to connect early career scholars to more senior folks. They also give really wonderful and substantive feedback. Sheldon is quite famous for his red pen, and Sandy read many, many drafts of my books.

Although Sheldon is an economist by training, he engages seriously with sociology, psychology, political science, and history. This approach is really important for me now as dean of a policy school. Although I have my own disciplinary and interdisciplinary training, my “team” is team excellence.

S&H: How would you describe your scholarship?

I consider myself an organizational sociologist. I’m interested in how institutions function and the ways in which formal processes like rules, policies, and missions sometimes collide with the informal processes of norms, values, and beliefs—and the structures of inequity that make it so tensions and pain points emerge within institutions. I’m interested in how the institutions that make up different systems operate and what they mean for people’s lives. They can be places of huge opportunity, but they can also be extremely damaging and destructive in ways that take people generations to recover.

I also consider myself to be a Black studies scholar, a women’s and gender studies scholar, and a scholar of inequality. This interdisciplinary approach allows me to communicate ideas across training and disciplinary styles, and I understand the stakes involved in different debates. It helps a lot in administration to have such a broad background. I’m really comfortable moving within all of those worlds and spaces.

S&H: You interviewed 100 women in Chicago living with HIV/AIDS for your award-winning book, Remaking a Life. What did you learn?

I think Remaking a Life pushes back on some core assumptions that we make as a society about safety nets. Yes, many of the people I interviewed received health care and social services, but the unique safety net they have access to through the Ryan White CARE Act also provides access to some economic assistance, social support, and pathways for political and civic engagement in places where the policy implementation is robust and effective. This particular configuration of services gives people a voice and agency for political and community change—and that can lead to transformative change.

One of the key ideas I highlight is how the women I interviewed confronted injuries of inequality—big and small wounds created by inequity, in which people’s race, class, gender, sexuality, and a variety of other statuses disproportionately exposed them to injury and harm. Part of what I became equally interested in was the transformation that’s possible when safety nets are there.

S&H: Tell us about your methodology as a scholar and a leader.

At the center of my research is humility and an understanding of where my knowledge comes from. My competence becomes excellence when I really listen and pay attention, because that's how I get my data. A really good researcher understands the power of listening and the power of processing.

A really good researcher understands the power of listening and the power of processing.”

They also understand the interrelationship that happens in knowledge production. I’m known in my interviews to actually share with my respondents some of my key theoretical musings and get their reactions to it and allow them to push back, sharpen, and add to it. My respondents in Remaking a Life, the community in which I studied, knew what the argument was before the book came out because we had been in conversation about it throughout the process and as I was formulating my ideas. I have an iterative approach to how I come to my conclusions, which I think is grounded in humility.

As dean, I’m doing the same thing. I’m listening, watching, and observing. I’m processing, saying what I think, and then I want to hit the ball back and forth. We create ideas together. It’s very much a team approach.

I found Ford intriguing at a scholarly level: How does a person who has such a rich and layered life become largely known for one thing (Ford’s pardoning of Richard Nixon)?”

S&H: You’ve become a bit of a Gerald Ford buff. What has caught your interest, and how might his story matter to students?

In my interim year as dean, I met with people who had personal relationships with Gerald Ford and who were involved in his legacy work. I became a field worker again, coming with humility, listening, and thinking about how to make connections. I found Ford intriguing at a scholarly level: How does a person who has such a rich and layered life become largely known for one thing (Ford’s pardoning of Richard Nixon)? How do we make space for the layers that policymakers bring to the table, when our discourse often seeks to flatten? And how do we unpack that more complicated and nuanced life and put it into context with a very contemporary conversation about the future of the Ford School? How do we make Ford’s life and legacy “legible” to students?

So I started researching and reading. Gerald Ford’s career was marked by complexity. He often talked to people on “the other side”—Democrats, and also Republicans within his own party who had very different ideas about how the country should be going forward, as well as people with different demographic backgrounds.

In one of my weekly Sunday night messages that I wrote to the Ford School community, I reflected on Ford’s childhood and some family disruption that he experienced in the early years of his life. Ford no doubt experienced social advantages and privileges, but there is also a story there that I think we all can connect to about the support system necessary to build a life of accomplishment, even when we’re coming from experiences of trauma.

S&H: What do you believe is the future role of public policy schools?

We are at a moment of such deep challenge. When you think about things that I believe are existential threats: climate; the future of democracy; the role of technology; and our ability to appreciate and embrace diversity alongside equity, inclusion, and belonging. We’re at a really important inflection point. We need people who have an understanding of how to connect with those with whom they disagree. We need people who can find ways to work together despite those differences.

I want to continue to advance the Ford School’s reputation, to be able to hold excellence and access together at the same time. My vision is moving us even closer to being ready to meet the moment.

Accolades and leadership

- Watkins-Hayes’ Remaking a Life won the American Sociological Association (ASA) Distinguished Book Award (the discipline’s highest book honor), the Eliot Freidson Outstanding Publication Award, numerous ASA section awards, and more

- U-M Center for Academic Innovation Advisory Council member

- Executive advisory board member, Wallace House Center for Journalists

- Board member, Russell Sage Foundation

- Former trustee, Spelman College, where Watkins-Hayes led the search process for the college’s 10th president

More in State & Hill

Below, find the full, formatted fall 2023 edition of State & Hill. Click here to return to the fall 2023 S&H homepage.